Language and literature

During the month of July, the Schuman Centre republishes the drafts of Jeff Fountain’s coffee-table book aiming to promote the centrality of the Bible’s influence to our Western way of life and thinking.

No book can compare to the influence the Bible has had on the development of languages and literature: in Europe east and west, in the Middle East over two millennia and globally over the past four centuries. The Bible has been translated into more languages than any other book. It is quoted in literature more often than any other source.

The Bible was translated in the first centuries CE from Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek into Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopian, Gothic and Latin languages.

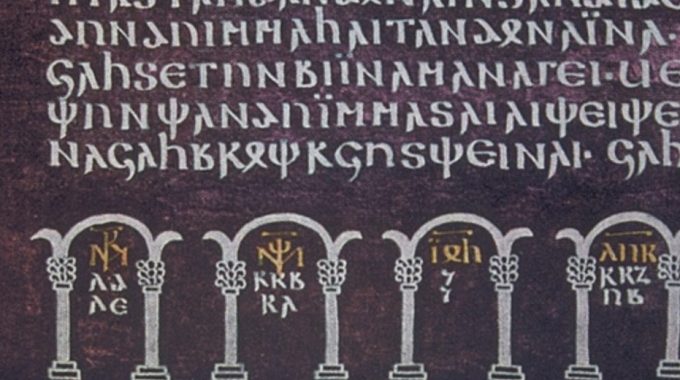

Ulfilas created the Gothic alphabet in the 4th century especially to translate the Bible (see photo). Jerome’s Latin translation later the same century became the standard Bible for the Roman Catholic Church up until modern times. Roman-oriented Slavic peoples, including Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes and Croats, adapted the Latin alphabet to their own languages.

Slavs of the Eastern Orthodox faith used the Cyrillic alphabet developed for Bible translation in the 9th century by the Greek missionary brothers Cyril and Methodius. Today more than 50 languages use Cyrillic letters, including Belarusian, Bulgarian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Russian, Serbian, Tajik, Turkmen, Ukrainian and Uzbek.

With an authoritative standard text, diverse dialects gave way to formalised spelling and unified usage. This process began later in western Europe with the Reformation idea that all should have access to the Bible in their native language.

Erasmus intended for his 1516 parallel translation of the New Testament in Greek and Latin to help others translate the Bible into native European languages. Using newly-surfaced manuscripts brought to the west by monks fleeing the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, he dared to correct many errors in Jerome’s Vulgate and shocked establishment Europe.

Aided by the newly-invented printing press, full Bible translations appeared very soon after in Belorusian (Skaryna, 1517), German (Luther, 1522), French (LeFevre d’Étaples, 1530), English (Coverdale, 1535), Swedish (Gustav Vasa, 1541) and Polish (Brest, 1563).

Over the following centuries, the Bible was translated into every European language. Today the entire book is available globally in 554 languages, more than any other book, with parts of the Bible in some 3000 languages.

A rich legacy of biblical proverbs, phrases and words thus became part of daily language in many European cultures. The English language is greatly indebted to William Tyndale whose 1526 New Testament translation completed in exile on the Continent made up 90 per cent of the King James Version of 1611. A master linguist skilled in the use of the monosyllable, Tyndale has given us many phrases used daily around the world, including:

Gave up the ghost, Let there be light, My brother’s keeper, Under the sun, Signs of the times, Lick the dust, Fall flat on his face, The land of the living, Let my people go, Out of the mouth of babes, Put words in thy mouth, Feet of clay, No peace for the wicked, A fly in the ointment, Wheels within wheels, Pour out one’s heart, The apple of his eye, Fleshpots, Go the extra mile, The parting of the ways, Eat, drink, and be merry, In him we live, and move, and have our being, Salt of the earth, An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, Fought the good fight, Turned the world upside down, God forbid, The powers that be, Filthy lucre, Take root, The blind leading the blind…

Up to a generation ago, English first names were officially called ‘Christian names’. How many in our circles of family and friends have names from the Bible or Christian history? e.g. Adam, Eve, Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob, Rachel, Joseph, Aaron, Miriam, Joshua, Ruth, Esther, Jonathan, David, Jonah, Daniel, Samuel, Elisabeth, Andrew, Peter, John, James, Mary, Ann (and countless variations of these two names), Matthew, Mark, Paul, Luke, Thomas, Steven, Philip, Timothy, Antony, Christopher, Christine, Catherine, Margaret, Martin, Patrick, Monica, Veronica, …

The Bible itself is literature, covering history, narrative, poetry, letters and visionary writings. It has also inspired some of the most influential books written in history, including The City of God (Augustine), Ecclesiastical History (Eusebius), An Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (Bede), The Divine Comedy (Dante), Paradise Lost (Milton), Pilgrim’s Progress(Bunyan), Faust (Goethe), A Christmas Carol (Dickens), The Brothers Karamazov(Dostoyevsky), Lord of the Rings (Tolkien) and the Narnia series (Lewis).

Shakespeare, raised on the Geneva Bible of 1560 and rumoured to have contributed to the KJV, quotes from the Bible some 1350 times, alluding to at least 42 bible books in his works.

Countless books and academic research papers continue to be written about the Bible, some even in strong opposition to its message. Yet to ignore the Bible is to embrace ignorance of our rich linguistic and literary heritage.

Truly the Bible has nourished the soul of European language and literature like no other book.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

For more weekly words from Jeff, visit weeklyword.eu.

This Post Has 0 Comments