Ethics and morals

During the month of July, the Schuman Centre republishes the drafts of Jeff Fountain’s coffee-table book aiming to promote the centrality of the Bible’s influence to our Western way of life and thinking.

What influence has the Bible had on the development of ethics and morals in western society?

Ethics and morals are words often used interchangeably, both relating to the ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ of conduct. But they are, in fact, different.

Ethics, from the Greek word ethos meaning ‘character’, refer to rules from an external source of social system, such as the workplace, a religion or a profession. Morals refer to internal, personal principles of right and wrong. The word derives from the Latin words moralis, mos, mores, meaning ‘custom(s)’.

Societies developed various codes of ethics and morals long before the Bible was completed. The concept of natural law was expounded by Greeks (e.g. Aristotle) and Romans (e.g. Cicero) on the use of reason to deduce rules of moral behavior from nature or God’s creation. The Hippocratic Oath, for example, is a code of ethics for doctors and nurses dating from the fourth or fifth century BC.

Paul, writing to the Romans, acknowledges this concept as an inbuilt moral compass: ‘when Gentiles, who do not have the law, do by nature things required by the law, they … show that the requirements of the law are written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness, and their thoughts sometimes accusing them and at other times even defending them.’ (2:14,15)

With the Christianisation of the European peoples over most of the first millennium, the Bible introduced an understanding about God and humans that transformed the worldviews of Greeks, Latins, Celts, Franks, Slavs, Vikings… virtually all Europeans. That humans were created with intrinsic dignity in God’s image, possessing moral equality before God, carried profound implications for social life.

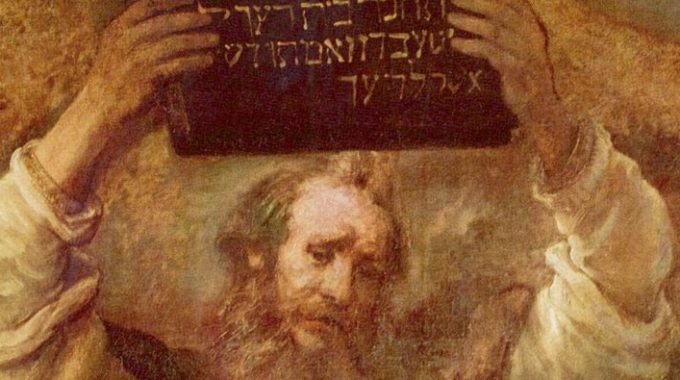

Gentile ‘barbarians’ became exposed to the Hebrew moral code we know as the Ten Commandments. These may simply have been ten verbs, Ten Words, each with a negative prefix: something like: ‘No-idols’, ‘No-murder’, ‘No-adultery’, ‘No-stealing’, ‘No-lying’, ‘No-coveting’… easily counted on one’s fingers. As Thomas Cahill writes, ‘they have been received by billions as reasonable, necessary, even unalterable because they are written on human hearts and always have been. They were always there in the inner core of the human person–in the deep silence that each of us carries within.’

Jesus reaffirmed the two-part summary of this code as found in the Torah (Deuteronomy 6:4-9 and Leviticus 19:18): namely, to love God with all one’s heart, mind, strength and soul, and to love one’s neighbour as oneself. Love for God and neighbour were interwoven. Without love for God, what grounds would there be for loving one’s neighbour?

Early Church Fathers, from Justin Martyr to Augustine of Hippo, drew their ethics from the Bible but also from the principles of Greek philosophy and Hellenistic Judaism. Medieval Christian philosophers like Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas, while building on Aristotle, argued that since human reason could not fully comprehend the Eternal law, it needed to be supplemented by revealed Divine law.

Reformers like Luther and Calvin set out to construct an ethical system solely from the Scriptures. For Calvin, the whole of human nature was corrupted by sin. Like Luther, he saw reason as no reliable guide for human conduct and rejected the view of classical philosophy and medieval scholasticism.

Other Protestants however, like Luther’s close colleague Philipp Melanchthon, still drew from Aristotelian philosophy; the Dutch Arminian, Hugo Grotius, based his foundations for international law on natural law.

Today theists and atheists still debate whether or not ethics and morals have sufficient grounds without God. Russian author Fyodor Dostoevesky, himself a believer, posited the question, ‘why should I live righteously and do good deeds, if I die entirely on earth? If there is no God, then everything is my will and I must express my will.’ German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche concurred: since God was dead, only might was right.

The Bible’s influence on the West’s moral legacy can be confirmed by surprising sources. BBC documentary presentator Niall Ferguson quotes scholars from the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences, who researched reasons for the West’s global dominance. After considering the West’s weapons, politics and economics, they concluded ‘that the heart of your culture was your religion: Christianity. The Christian moral foundation of social and cultural life was what made possible the emergence of capitalism and then the successful transition to democratic politics.’

Our last word comes from secular German philosopher Jürgen Habermas: ‘Universalistic egalitarianism, from which sprang the ideals of freedom and a collective life in solidarity, the autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct legacy of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love.’

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

For more weekly words from Jeff, visit weeklyword.eu.

This Post Has 0 Comments