Business and Economics

During the month of July, the Schuman Centre republishes the drafts of Jeff Fountain’s coffee-table book aiming to promote the centrality of the Bible’s influence to our Western way of life and thinking.

The Bible may seem for many to be far removed from the world of business and economics. Yet our modern economy has been profoundly shaped by both the Old and New Testaments through the ages.

One contemporary economist calls our present day market capitalism ‘a secularised offspring of Hebrew and Christian tradition, beliefs and hopes’. Our belief in fairness, protecting the weaker from the stronger, our hope of a better future, our belief in human dignity and in freedom, as well as adherence to legal rules, stem from the Bible, not from secular scientific textbooks.

Economics is not value-free mathematical inquiry, as guru Milton Friedman would have us believe. Ultimately it is about choosing between good and evil. The Bible is full of economic thinking and norms, with over 700 references to money and economics. Think of Joseph and his introduction of the first seven-year economic plan in recorded history. Think of the Mosaic law, the proverbs and the prophets who addressed attitudes to wealth and possessions, stressed brotherly love, family duties, the common good and social responsibilities, especially to widows, the poor and sojourners. Recall the institution of the Jubilee year, in which after every forty-nine years debts were cancelled and lands were returned to the original owners, restricting the accumulation of wealth in the hands of the few and ensuring a level playing field for all.

Jesus told many stories about attitudes to money, wealth, poverty and spiritual values. Almost two thirds of the parables concern socio-economic contexts: the rich fool, the two debtors, the unjust steward and many more. He talked about rendering to Caesar what was Caesar’s and to God what was God’s. His command ‘to love God and love your neighbour as yourself’ has shaped western economic attitudes through the teachings of the Church, restricting unbridled greed and promoting a social conscience in the community.

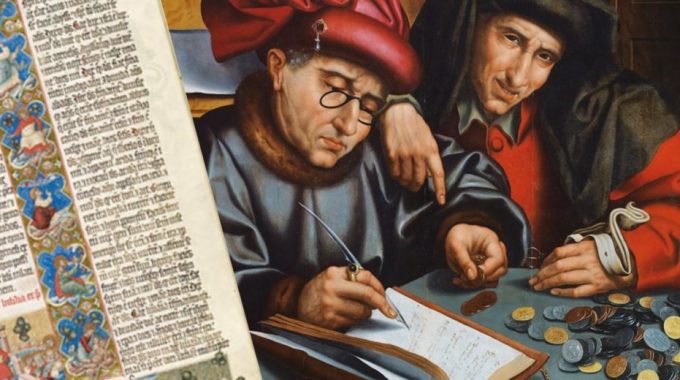

Terms such as ‘credit’ and ‘debt’ were derived from spiritual concepts: ‘credit’ from ‘credo’, I believe; ‘debt’ also meaning ‘sin’ or ‘guilt’ in various European languages. (e.g. ‘forgive us our debts…’). Talking of credit and debt, the double-entry bookkeeping method now deployed globally was developed by a Franciscan friar, Luca Pacioli, to restore God’s order into the chaos of his own financial world.

Global charts and maps showing the quality of democracy ranking, the Gross National Product per capita, or the Transparency International Index showing the least corrupt nations, reveal a striking pattern. Topping each of these lists are the nations most shaped by the Bible through the Reformation (even if largely secular today), followed by Catholic countries, then Orthodox, and eventually Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, communist and animist nations.

Although no fan of John Calvin, Max Weber traced the roots of capitalism to the Geneva Reformer’s strong work ethic, his emphasis on self-control and reverence for the biblical commands to not steal or covet, which gave foundations for private ownership and free enterprise. Calvin’s allowance of a modest four percent interest rate on loans lasted for four centuries in Switzerland, one of the long-term sources of Switzerland’s prosperity.

Adam Smith, often called the father of modern economics for his ground-breaking book The Wealth of Nations, was a professor of Christian moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow. He also wrote about the centrality of the concept of mutual sympathy, or empathy, the moral faculty that held self-interest in check.

Modern economics, broken loose from the ethical restraints Smith assumed, is causing dissatisfaction the world over. Yet the biblical texts, foundational to our western civilisation, remain a forgotten code offering timely and practical guidelines for a more just and equitable economic order.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

For more weekly words from Jeff, visit weeklyword.eu.

This Post Has 0 Comments