From chaos to order

During the month of July, the Schuman Centre republishes the drafts of Jeff Fountain’s coffee-table book aiming to promote the centrality of the Bible’s influence to our Western way of life and thinking.

Set in the Garden of Eden, the opening chapters of Genesis record God’s first instructions to human beings to multiply, be fruitful and care for the earth.

The task of bringing order out of chaos, of nurturing fruitfulness and productivity was part of the ‘creation mandate’ given to the human race, even before Adam and Eve had disobeyed God.

However, their wilful rebellion alienated themselves from their Maker, each other and their environment. Somehow it affected all of creation. God tells Adam, ‘Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat food from it all the days of your life. It will produce thorns and thistles for you, and you will eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food.’ (Gen. 3: 17-19)

Agriculture and gardening continue in the background of the biblical story, of patriarchs with large flocks, of tribes settling in the Promised Land raising herds and crops, and of prophets who foretell of streams in the desert, of parched land becoming orchards, of wildernesses blossoming as the rose and of evergreens, elms and cypress trees triumphing over wasteland. Jesus explained spiritual truths with stories about soils, sowers, weeds, vineyards and sheep.

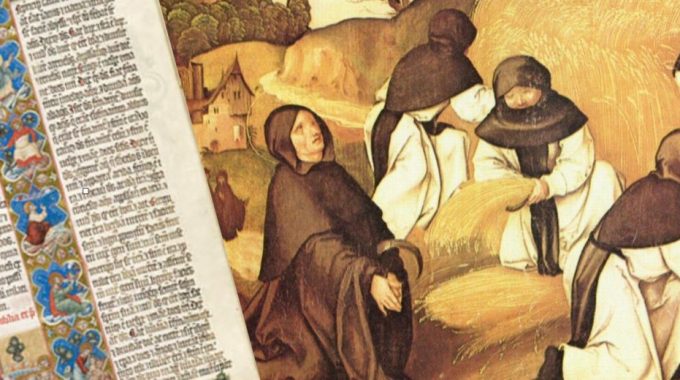

This biblical vision of turning chaos into order and barrenness into fruitfulness spurred the monastic communities which spread to Europe from the Egyptian deserts. The monastery became the building block of the new order emerging from the collapse of the Roman Empire. From Ireland to Armenia, these communities developed a daily rhythm of prayer and work, ora et labora. Wilderness was transformed into arable farmland as monks built dykes, drained swamps and taught local peasants agricultural skills in obedience to God’s creation mandate. Monks cultivated vineyards for wine and grew hops for beer, activities still associated with monasteries today.

Monasteries developed several types of gardens. The cloister garth was a square garden at the heart of the monastery surrounded by cloisters. A sacristan’s garden produced flowers for the altar, sometimes doubling as the paradise, at the altar end of the monastery church, a place of beauty reminiscent of the lost Garden of Eden. Most monasteries also had vegetable gardens and gardens of medicinal herbs. One famous medicinal garden was nurtured by the extraordinary Abbess Hildegard of Bingen on the Rhine, who saw herbs, spices, and foods as God’s gifts to keep humans healthy and peaceful.

Elaborate gardens would later become associated with castles and palaces. In more recent times, gardens developed into common places in cities for all to enjoy as places of beauty, rest and recreation. Gardening and agriculture are activities unique to humans, reflect the Creator’s image and express the biblical mandate to care for our planet.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

For more weekly words from Jeff, visit weeklyword.eu.

This Post Has 0 Comments