The Children’s Champion

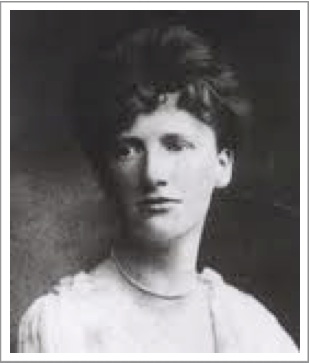

Eglantyne Jebb was an unlikely person to found ‘Save the Children’. After her first year of teaching in 1900, she confessed she didn’t care for children, ‘the little wretches’. Yet she was to become the pioneer of children’s rights and the initiator of what grew into the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

And it all began with a vision of Jesus.

I came across this remarkable story recently researching for a paper on human rights I had been asked to submit for a compendium to be published by the Centre for Children’s Rights of the University of Amsterdam. The foundational document for this centre is the CRC, which has been ratified by almost every UN member except the US. Some American Christians, for example, suspect the CRC of being anti-family and overempowering of children, despite its affirmation of the rights of parents.

So it may be surprising to discover the spiritual experience that transformed this woman’s heart towards children.

After studying history at Oxford, Eglantyne went into a frustrating year of teaching, before moving to Cambridge to care for her mother. In 1913 she was asked to help raise funds for relief work in Macedonia, a project which opened her eyes to the plight of children victimised by strife.

When the First World War broke out, Eglantyne Jebb, and her sister Dorothy, (married into the Buxton family we have mentioned in the last two ww’s) were appalled by the climate of jingoism in Britain which demonised the enemy. Conscious of the plight of children affected by the hostilities, the sisters published weekly ‘notes from the foreign press’. After the war ended, the sisters continued to oppose the British blockade of Germany and the former Austrian-Hungarian Empire resulting in starvation and the spread of sickness.

Defiant

In the vitriolic spirit of Versailles, the British government was in no mood to go soft on the defeated enemy. So when Eglantyne distributed a leaflet in Trafalgar Square accusing the blockade of causing babies to starve, she was arrested and fined.

The defiant sisters however proceeded with plans for a public meeting in May 1919, in the Royal Albert Hall, to set up a Save the Children Fund. The British public responded with giving hundreds of thousands of pounds overnight to start the fund to help suffering children.

The fund was not expected to be permanent, but to respond to the current emergency. Using page-length newspaper advertisements, and film-footage of famine and disaster regions like Germany, Austria, Hungary, France, Belgium, the Balkans and among Armenian refugees in Turkey, the sisters began to influence public opinion and become a force for the government to reckon with.

Eglantyne proved to be a charismatic, persuasive and committed leader, shaping Save the Children into an effective relief agency delivering food, clothing and money efficiently and quickly where it was needed.

Believing that the rights of a child should be especially protected and enforced, Eglantyne wrote: ‘I believe we should claim certain rights for the children and labour for their universal recognition, so that everybody who in any way comes into contact with children, that is to say the vast majority of mankind, may be in a position to help forward the movement.’

Inspiration

In 1923 she drafted The Declaration of the Rights of the Child, the first-ever list of child’s rights, including the right to be the first to receive relief in times of distress.*

These ideas were endorsed by the League of Nations in November 1924. Thirty-five years later, in 1959, the United Nations General Assembly added ten principles in place of the original five to endorse a new version of the Declaration. Another three decades passed before the CRC was adopted by UN General Assembly. On September 2, 1990 it became international law.

Eglantyne Jebb died in Geneva in 1928 from a thyroid disease that had caused fatigue for much of her adult life. Despite this condition, it was an experience she had had in her twenties that motivated her to work tirelessly on behalf of suffering children. During a difficult period, she wrote that ‘in my trouble there came to me the face of Christ’. Her biographer writes that ‘for Eglantyne, finding Christ in her midst was a spiritual epiphany of the profoundest significance. She was now confident she had been chosen to do God’s work.’**

This was an experience she drew from for the rest of her life. When facing a challenge or a question, she would simply ask herself, ‘What would Jesus do?’

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

* see www.un-documents.net/gdrc1924.htm

**The Woman Who Saved the Children, by Clare Mulley

This Post Has 0 Comments