Our New Heroes

Almost overnight, thanks to a deadly unseen intruder, a new category of people emerged a few weeks ago whom we now call ‘essential workers’. While everyone else stayed safely at home, these new heroes (wo)manned the barricades and ran the trenches by risking the hospital wards, driving public transport, delivering mail and orders-by-post, stocking the supermarket shelves and keeping the systems going.

In the first weeks of the crisis, we saw public displays of appreciation for such ‘vital professions’ on television with clapping from doorways, windows and balconies, or clanging of pots and pans. Some of these ‘life-savers’ themselves paid the ultimate price doing their best ‘in the line of duty’. Nurses, doctors, pastors, police and transport workers have been among the victims of COVID-19.

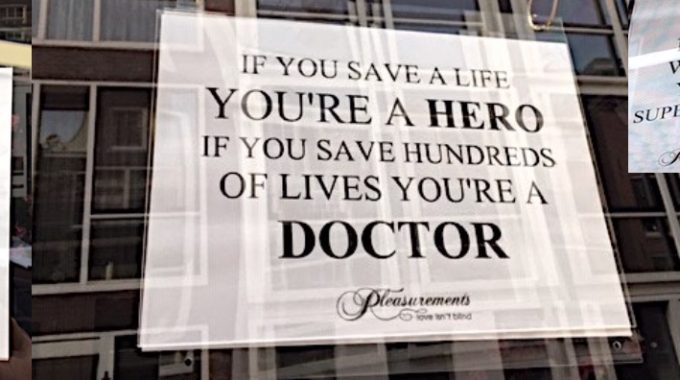

The posters in the photo above I came across last week in an Amsterdam shop window reflect a new public awareness of those who are serving others day after day, not simply out of naked self-interest, as neo-liberal economists would have us believe about human behaviour. That might be true for many economists, hedge fund managers and bankers (none of whom are ‘essential workers’), but it is not true for many who are proving to be the glue of community.

Less heroically, other pastors have died of the virus after holding packed church services declaring ‘that God was bigger than COVID-19’. A number of high-profile politicians have also tried to appear heroically defiant, among them Boris Johnson, who, soon after urging Britain to ‘send coronavirus packing in just 12 weeks’, himself lay in intensive care fighting for his life.

British journalist Tom Holland speculated recently in UnHerd.com that Johnson may have had a sort-of sick-bed conversion experience. Perhaps not a Damascus Road experience, yet Holland detected ‘hints in the speech that (Johnson) gave after being discharged from hospital that his personal experience of COVID-19 has served to recalibrate his take both on the virus and on those who are daily risking their own lives to fight it.’

“It is thanks to that courage, that devotion, that duty and that love that our National Health Service has been unbeatable,” the recovered patient had told reporters. “Salus populi suprema lex est” Boris is said to have told ministers and health officials later, offering his own translation of Cicero’s quote: “the health of the people should be the supreme law”.

No-one really knows where this pandemic will lead us all. No doubt to different results in different places. Some rulers are increasing their hold on power opportunistically, while others are making embarrassing displays of their incompetence. Hopefully one result will be that better leaders elsewhere will be rethinking their politics because people everywhere will be demanding values affirming those things they have discovered to matter most: relationships, interdependence, solidarity and the pursuit of the common good.

Two weeks into lockdown, I wrote the following in ‘weeklyword’:

Threatening to rip society apart, the unprecedented challenge of the corona-crisis also presents an opportunity. Suddenly we have all realised our common vulnerability. Never in human history has our common fate been shown to be so interlinked – all seven-plus billion people on this planet. Our dependence on each other and the systems of society – local, national and global – have become obvious.

As the lockdown dragged on, the reality dawned that we were facing not just weeks and months but years of living with corona and its effects. The day before Johnson was driven to hospital, that venerable bastion of neo-liberalism, the Financial Times, ran a historic editorial admitting that the COVID-19 pandemic had ‘injected a sense of togetherness into polarised societies’, shining ‘a glaring light on existing inequalities’. The great test all countries would soon face, it predicted, was whether or not current feelings of common purpose would shape society after the crisis.

Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.

Wow! The FT and Boris, a double conversion! If 1989 was the watershed year for communism, surely 2020 will signal the demise of the Friedman-Hayek era of free-market economics. As Dutch columnist Rutger Bregman writes in De Correspondent, neo-liberalism saw people as egoists, which in turn led to privatisation, growing inequality and the erosion of the public sphere.

Its time for a more realistic view of humans as team players, and of economics as seeking the common good.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

This Post Has 0 Comments