A Swiss Hero

The Swiss, both Catholic and Protestant, esteem Nicholas von Flüe (1417–87) as the spiritual father of their country. Bruder Klaus, as he became affectionately known, was a farmer, soldier, councillor and judge who lived in Flüeli, the geographical centre of Switzerland in the alpine foothills south of Lucerne. Yet at the age of fifty, he felt God call him to leave his wife and ten children(!) to begin the life of a hermit and sage sought out for wisdom and advice by rulers from near and far.

Last month my wife and I spent several days in a cloister overlooking Lake Sarnen (renowned through a watercolour by J.M.W. Turner) with young aspiring Christian politicians. Poised on the alpine foothills in the village of Sankt Niklausen, the cloister was a short walk from the rift valley where Bruder Klaus spent the last twenty years of his life. Today hotels, lodges and restaurants spread long the edge of the rift catering to the needs of pilgrims arriving by foot, car and bus to pay their respect to this ecumencial saint. As early as 1470, while Bruder Klaus was still alive, his chapel was sanctioned by the pope as a place of pilgrimage, part of the Saint James Trail, a pilgrims’ route leading to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

Klaus already had a reputation for moral integrity and deep spirituality by the time he was thirty, when he married Dorothea Wyss. Although illiterate, he devoutly followed spiritual disciplines, fasting, rising early to pray and spending long periods in contemplation. His mother had introduced him to the spirituality of the ‘Friends of God’ (Gottesfreunde) a movement of lay and clergy which spread along the Rhine as far as the Netherlands. Their aim was union with God through prayer, meditation on the passion of Christ, renunciation, and the service of one’s neighbour.

Vision

Klaus fought in the Old Zürich War during which the canton of Zurich was prevented by other cantons of the Swiss Confederacy from leaving their alliance. Fifteenth-century Switzerland was still a collection of cantons at war with each other, especially forest cantons conflicting with the cantons of the towns. Klaus was to play a key role in preventing war among the cantons in the future.

A mystical vision of a horse eating a lily convicted him that he had been allowing earthly cares (the horse represented the daily chores of farming) to swallow his spiritual life (the lily being a symbol of purity). Together with his wife and five girls and five boys, he prayerfully decided in 1467 to devote himself to the contemplative life, and set off towards Alsace where the Gottesfreunde had communities. Lodging en route in Basel with a fellow ‘Friend’, Klaus was persuaded not to cross the border where he could expect to encounter hostility due to the reputation of the Swiss as ‘savage soldiers’. He returned to his home district and began to follow the path of obedience as a hermit. Seized with severe gastric pains, he found himself unable to eat anything except the elements of the Blessed Sacrament.

When once commanded by his spiritual superior to eat a meal, he became violently ill. According to the records, the only food he ate for the next twenty years until his death were the sacramental wine and bread. He once told the local parish priest, ‘The body and blood of Christ are my only food. He dwells in me and I in him. He is my food, my drink, my health and medicine.’ Both church and civil authorities spied on him to catch him out, but had to conclude his testimony to be genuine.

Counsel

Two years after leaving home and living in makeshift shelters, locals built him a little hut with a small chapel attached. I visited his cell last month with its two windows, one looking into the chapel to follow the mass services there, and the other where visitors would gather in the afternoons seeking his spiritual counsel. One such visitor was Albert von Bonstetten, dean of the monastery of Einsiedeln, who described the recluse as ‘tall, brown, and wrinkled, with thin grizzled locks and a short beard. His eyes were bright, his teeth white and well preserved and his nose shapely’. Several other contemporary reports and letters still survive.

At a crucial phase of the development of the Swiss Confederacy, when wars between cantons threatened the survival of the nascent nation, officials came to seek Klaus’ advice. His moral authority seems to have been the key factor in dissolving the rigid positions of the opposing sides. The resulting attitude of mutual tolerance prevented a self-destructive civil war and enabled the Swiss Confederation to remain united in the face of the divisive religious controversies to come.

Oh for spiritual fathers (and mothers) in Europe today!

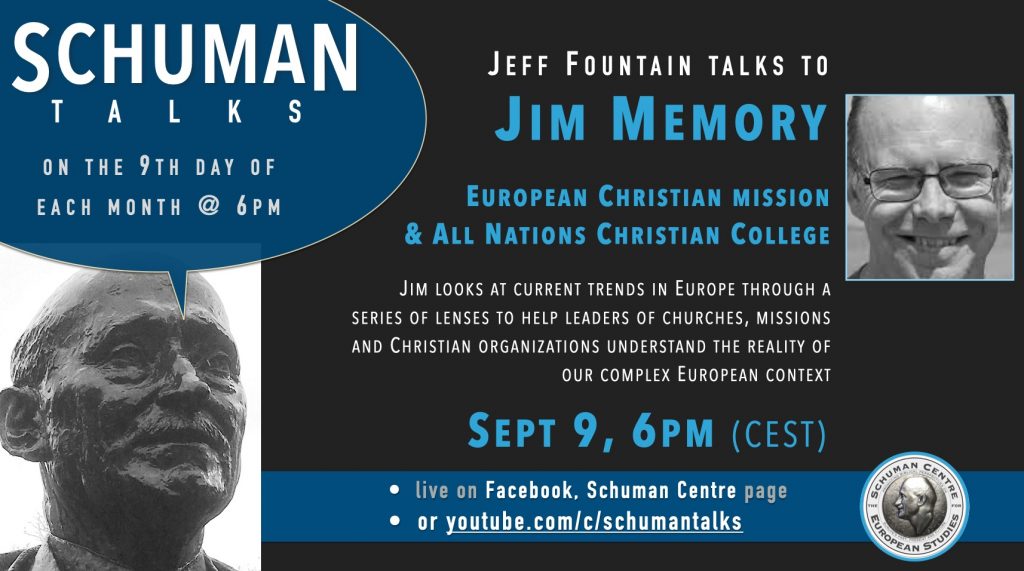

P.S. Make sure to hear Jim Memory’s talk from this week about his missiological report, Europe 2021.

This Post Has 0 Comments