Religious divisions that shaped Europe

The separations between the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches, and later on between the Roman Catholic and the Protestant churches have shaped the history of Europe. In this article, Evert van de Poll explores how those divisions have shaped our European nations up to this day.

This is an excerpt of Evert Van de Poll’s book ‘Christian faith and the making of Europe’. To be published soon.

The author Rémi Brague talks about a dichotomy that arose as Catholics in the west and Orthodox in the east became more and more separated from each other.

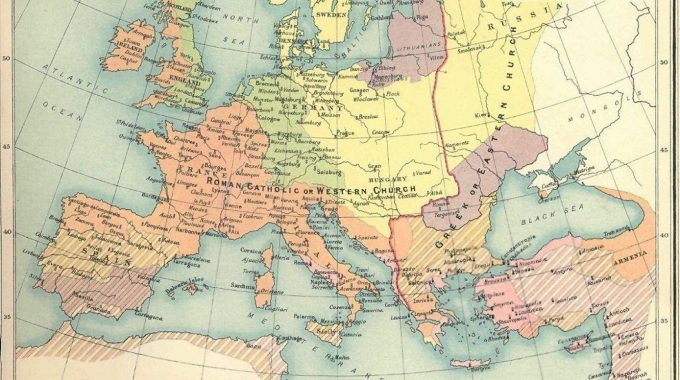

This led to a dividing line that started in the south, where the Romans had divided their Empire in a Western, Latin-speaking part, and an eastern Greek-speaking part. It separated the later Frankish kingdoms from the Byzantine Empire. It ran between Italy and Greece, and went right to the north, between the western and the eastern Slavic peoples, between Baltic and Finnish peoples on one side and Russians on the other. This delimitation continued to mark political divisions, right up until the First World War.

According to Brague, this has become the eastern limit of Europe. Samuel Huntingdon, in his famous book on the coming clashes between civilisations in the 21st century, also draws a line between the European and the Orthodox civilisation.

This view corresponds with a widespread prejudice that situates the heartland of Europe in the West, and tends to exclude Russia from the picture. Interestingly, the historical line between Catholic and Orthodox regions corresponds to a large extent with the eastern border of the present European Union. Moreover, there are many tensions between the EU and Russia. This often reinforces the idea that this is where Europe ends, but it simply is not true to the historical facts.

This would imply that Greece is not part of Europe, but that is absurd. Moreover, as Slovenian diplomat Leon Marc explains, convincingly, Orthodox Slavs are as much part of the European history as the Poles and the Slovaks. The Catholic part has a Latin and Roman orientation, while the Orthodox part further east is rooted in the Greek Christian culture of the Byzantine Empire (the continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire). We shall come back to the question of ‘Eastern Europe’ further on.

In the 16th century, a fourth dichotomy emerged, between countries dominated by Catholicism in the south and countries dominated by forms of Protestantism in the north. For more than two centuries, Catholic and Protestant princes fought each other in devastating religious wars. . Although they are generally called the ‘Religious Wars’ they were more motivated by political interests, competition for power and economic rivalry than by sincere Christian concerns, in a time when confessional affiliation were closely related to political allegiances. Moreover, the Catholic Church launched the Counter Reformation to push back the advance of Protestantism. The outcome of all this conflict was that Protestantism became the dominant confession in the north and in the northwest of Europe. Catholicism remained dominant in the southern and central-eastern parts of the continent.

This divide has led to important cultural differences. Sociologists generally follow the thesis of Max Weber that there is a link between the Protestant work ethic and the rise of capitalism. We observe that in Catholic countries, people have a different view of authority and governance – more hierarchical, more top down – than in Protestant countries – more room for personal initiative, more democratic.

Another difference is important to notice. In Catholic countries Protestants and other religious minorities have been suppressed or marginalised. On the contrary, there have been important Catholic minorities in several Protestant countries (Britain, the Netherlands) or regions (e.g. Westphalia and Bavaria in Germany). A problem in ‘Protestant’ countries was the position of Protestants not belonging to the mainline or state Church: non-conformists, dissenters, Baptists, Mennonites as well as Pietist and Evangelical movements that left the mainline Churches. For a ling time they were submitted to legal restrictions, in some cases even persecuted, but in the course of the 18th and 19th century, the plurality of Protestantism was gradually accepted and all Churches obtained full legal status. As a result, ‘Protestant’ countries have become used to religious plurality, which in turn has facilitated the development of pluralist democracy later on.

Finally, there is a difference in attitude towards the institutional Church among those who do not practice the Christian faith. In Catholic countries, many of them maintain some link with the Church, so that there is a higher percentage of nominal or nonpracticing Christians than in countries dominated by a Protestant tradition. In Protestantism, being a Christian is fundamentally a matter of personal faith rather than a matter of belonging to the Church and receiving the sacraments. People in a cultural realm influenced by Protestantism, who don’t share the basic Christian beliefs, will see less reason to remain affiliated to a Church. In these countries we observe higher percentages of non-affiliated or nonreligious people.

Dr Evert van de Poll

Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven and a pastor with the French Baptist Federation.

Image: public domain (source: Wikipedia)

This Post Has 0 Comments