One Story, One Book

The central message the Bible tells us is that Jesus Christ came on earth, died and rose again, to reconcile men and women to the Father. This message not only changed millions of lives, but also transformed Europe. In this article, Dr Evert van de Poll explains how this message shaped the Old Continent.

This is an excerpt of Evert Van de Poll’s book ‘Christian faith and the making of Europe’. To be published soon.

As Europeans we are very much aware of our diversity. We find ourselves amidst a mosaic of ethnic origins, languages, national and regional histories, political traditions, cultures, and lifestyles.

Most of us are strongly attached to our particular identity, feeling ‘European’ only in a secondary or an accessory way. Yet, we are part of this typical whole called Europe. Looked upon from the outside, the various populations of this continent have so much in common. Although every ethnic group and every nation on the continent has its own particular story to tell, and while they have fought each other bitterly and continuously, their histories are marked by some common denominators, so that we can speak of a combined history in which the fate of these peoples has been closely intertwined.

The first common thread in history was woven by the Roman Empire. It brought the southern regions together under the umbrella of an administrative system, and it spread the Greco-Roman culture which became a sort of layer over the existing local cultures and religions. This gave cohesion to the heteroclite population within its borders. However, it was a Mediterranean empire, even though it spread to the northwest as far as Britain. The larger part of what is now called Europe lay outside the empire. Adopting the cultural prejudice of the Greeks, the Romans called the ethnic groups beyond their borders, whether to the north or to the south, collectively ‘Barbarians’.

The second and even more important common denominator is the Christian faith. Since this became the official religion of the Roman Empire, in the fourth century AD, it has given a religious and cultural cohesion to the peoples within this empire. After the disorder following the downfall of the western part of the empire, the Church stood out as sole force of cohesion among its multicultural population and the host of invading tribes who, quite remarkably, adopted the religion of the people they had conquered or driven away.

Moreover, the Christian message was spread much further than the Roman armies had ever ventured, to the north and to the east. The same Story that had been told to Greeks and Romans was now also told to Gauls and Celts, Scots and Picts, Angles and Saxons, Frisians and Franks, Germans and Goths, Slavs and Rus’ and Vikings. They were integrated into the Christian realm, their frame of reference became the Christian religion and a Biblical religious worldview. Over the centuries this led to values and behaviours that have become known as ‘European’ and are now generally taken for granted as ‘normal’, ‘self-evident’.

So here we have ‘the two streams of history that have flowed into the life of Europe during the past two millennia’, as Lesslie Newbigin has formulated so well. On the one hand the stream flowing from classical learning and administrative structures, with its fountainhead in the history of the Roman Empire, and on the other hand ‘the stream that comes from the history of Israel mediated through the Bible and the living memory of this history in the life of the Christian Church’.[1] And he goes on to say:

What has made Europe a distinct cultural and spiritual entity is the fact that, for a thousand years, the barbarian tribes who had found their home there were schooled in both the Biblical story and the learning of classical antiquity, the legacy of Greece and Rome. Their intellectual leaders were taught in Greek and Latin, but the story that shaped their thinking was the Bible (…) The Biblical story came to be the one story that shaped the understanding of who we are, where we come from, and where we are going… And because Europe later developed that way of thinking and organising life which is now known throughout the world as ‘modernity’, we cannot understand modernity without understanding this part of our history.[2]

Lesslie Newbigin, Proper Confidence, p.3 and 13

From the Mediterranean islands to the abodes of the Vikings far north, from the Irish and Scottish shores way into the vast plains of Russia, people were telling and remembering the same story of Jesus Christ, following the same liturgical calendar, in popular drama and songs, in sculptures and paintings. The story of the One and only God who has created all things, who has revealed his word to the prophets and the apostles of the Bible, and who so loved the world that He sent his eternal Son as the Saviour of all, Jesus the Christ, who became a man like us, who died on a cruel cross for the sins of mankind, and to raise from the dead, in order to reconcile men and women all over the world with God and give them eternal life.

This story of Jesus Christ was transmitted everywhere. In whatever language or custom it was couched, in whatever theology it was expressed, it was basically the same all over Europe. Historian Norman Davies concludes: ‘This laid the foundations for what was to emerge as a self-conscious geographical unity calling itself Europe, distinct from its Asian background’.[2] (He is referring to the fact that the many tribes had originally migrated from Asia.)

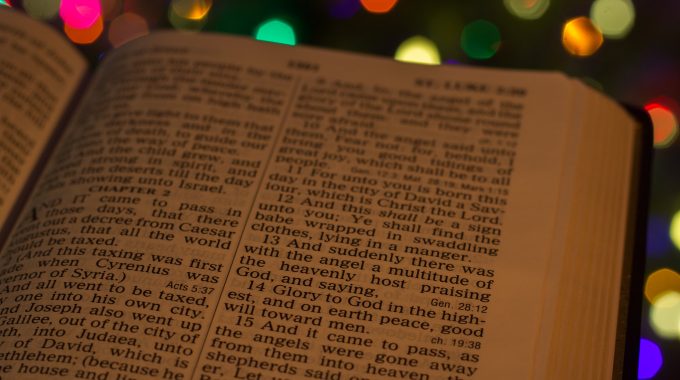

With the Story came the Book. For a long time, the Bible was read by the learned only and the clergy transmitted its stories orally to the common people. Then came the printing press, which made the Bible available to ordinary Christians in their own language. Not only has it remained the absolute best-seller until the present day, it has become the most important source of inspiration for shaping the social, cultural and religious landscape of Europe. There is a tendency among intellectuals today to downplay this influence and to pretend that modern Europe is rather shaped by the ideas of Humanism and the Enlightenment. They often forget that these movements were deeply rooted in Christian moral teaching. The ideas based on this Story and this Book have even profoundly influenced the secular world-view and the secular public sphere of today.

Dr Evert van de Poll

Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven and a pastor with the French Baptist Federation.

Picture: Public domain, www.flickr.com

[1]Lesslie Newbigin, Proper Confidence, p. 2.

[2]Norman Davies, Europe, p. 216.

This Post Has 0 Comments