Europe's remarkable diversity

Europe is like a big patchwork of languages, nations, histories or ethnicities. This diversity can be a challenge to understanding of Europe. In this article, Dr Evert van de Poll explores some aspects of Europe’s diversity.

This is an excerpt of Evert Van de Poll’s book Christian faith and the making of Europe. To be published soon.

Diversity is indeed a remarkable aspect of our continent. We are a mosaic of ethnic identities, languages, national histories, political traditions, cultures, and lifestyles.

Ethnic diversity

As far as ethnic origins are concerned, Europeans are a mixed rabble indeed. Their forebears came from the east, long before the beginning of the Christian era. Then there was the period of ethnic upheaval called ‘the great people movements’, towards the end of the Roman Empire and in the centuries following its downfall. As a result, a great ethnic diversity emerged: besides Romans and Greeks, there were Celts, Scots, Bretons, Picots, Russians, Longobards, Saxons, Franks, Burgundians, Germans, Slavs, Ostrogoths and Visigoths, Frisians, Danes, Vikings and more. All these tribes spoke a variety of languages, had very different modes of life, and worshipped a host of gods.

Throughout history large numbers of people have migrated from one part to another, often fleeing political upheaval, economic hardship or religious intolerance or a combination of these. Today there is an incessant influx of non-European migrants, making the ethnic picture even more complex. Tensions between the modern nation state and minorities within its borders are a recurrent phenomenon.

Linguistic diversity

Europe is also marked by the linguistic diversity of its inhabitants. When the European Parliament meets in Strasbourg, all deputies wear headphones, enabling them to listen to the simultaneous translation of what others are saying. Speakers are proud to use their mother tongue to express their opinions. Hundreds of translators are busy interpreting what each of them has to say, into the twenty or so official languages of the European Union. To American or Chinese observers, this sounds crazy. But for Europeans, this is normal. This is precisely what makes us Europeans: we communicate and cooperate in a multilingual way because we do not want one language and one culture to dominate the rest. To preserve our diversity, we accept that many different languages are used. So we try to learn one or two other languages, and we translate. As the interaction between the peoples of this continent increases, there is an ever-growing demand for interpreters and translators. This is typical of the way we are doing things in this part of the world. A saying attributed to the Italian author Umberto Eco sums it up very well: ‘Europe is translation.’

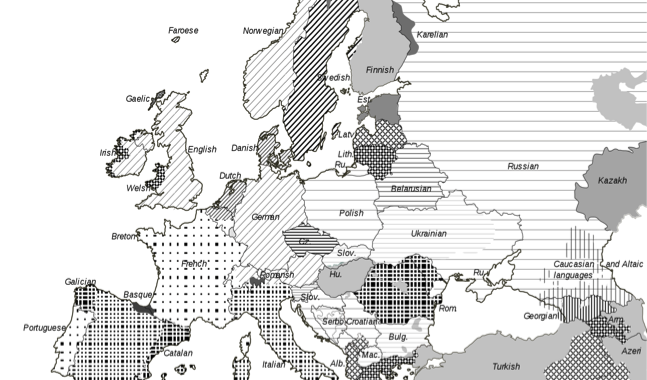

Europe’s linguistic diversity is a major obstacle to its economic cooperation and political integration. Yet others insist that it is an asset, a cultural richness. Because the European Union endeavours to maintain this diversity at all levels, it is held out as a model for other regions of the world where countries are separated by linguistic and cultural borders. The map above shows the linguistic variety.

There are three main language families: Latin or Romance (various forms of dots in squares), Germanic (oblique lines) and Slavic (horizontal lines). Scattered among these are other languages, some of them are akin to each other (Basque, Celtic languages in Ireland and the United Kingdom, Finnish, Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian, Albanese and Greek, Hungarian, Turkish.)

The geographical distribution of languages is such that we can distinguish three major linguistic zones: ‘Latin’ in the southwest, ‘Germanic’ in the northwest, and ‘Slavic’ in the east. Notice the mosaic of languages in the southeast.

Diversity of histories

A major element of culture is the collective memory of historical events that shaped the conditions of life of the people. Again, Europe is marked by a diversity of historical experiences. Every European country has its own historical experienceand therefore its own memory of the past. Their particular histories have been determined by geographic location, economic developments, wars and invasions, political rivalry and alliances. The memory of the Poles, for instance, is marked by submission to the surrounding peoples: Prussians, Austrians and Russians. The common memory of the Italians is marked by ages of internal division and the fact that its capital is simultaneously the institutional centre of the worldwide Roman Catholic Church. The memory of the Germans is marked by the clashes between Protestant and Catholic princes, and the fatal imperial ambitions of the Second and the Third Reich. While some nations have a long history, going back to the High Middle Ages (England, France), others have been established much later. Belgium was created in 1830, Slovakia in 1991.

Dr Evert van de Poll

Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven and a pastor with the French Baptist Federation.

Picture: Public domain, wikimedia.org – File: Languages_of_Europe_(BW).png

This Post Has 0 Comments