Speaking with God

How can we nourish our own spiritual lives through drawing from historical wells? This was the focus of our daily meditations during the Masterclass in European Studies last week in Amsterdam.

With a dozen participants from five European countries, we explored some of the many rich resources often neglected in free church circles, some from as far back as the Desert Fathers and the Early Church Fathers.

Henri Nouwen described the voices of the old Egyptian hermits as expressing a wisdom, hidden from the learned and revealed to mere children, and worth searching for. Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote that the spirituality of the desert fathers and mothers resonated strongly with questions many ask today: How can we discover the truth about ourselves? How do we live in relationship with others? What does the desert teach us about priorities?

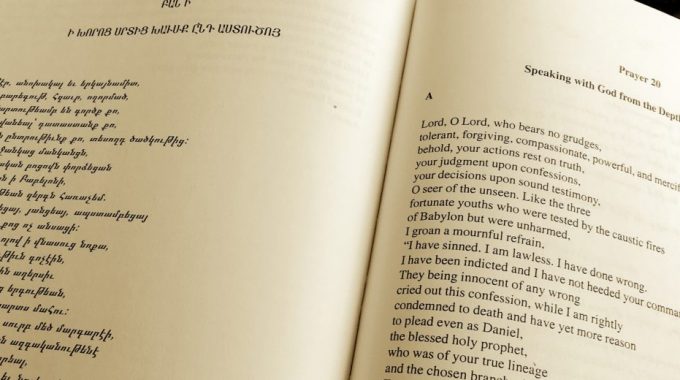

One rich tradition is that of the Church of Armenia, the first nation to embrace Christianity officially in 301, before Constantine became emperor. Here was a tradition strongly influenced by the Coptic tradition of Egypt. On a trip to Armenia nearly twenty years ago, I met Thomas Samuelian, the translator of a one thousand-year-old classic in Armenian devotional literature, by St Gregory of Narek, called ‘Speaking to God from the depths of the heart’. I have never come across such rich, descriptive, eloquent, imaginative, articulate and original language as in this thick volume, with original Armenian script on the left page, and the English translation on the other (see photo). Our contemporary worship language seems so pale in comparison.

St Gregory’s Book of Prayers have been compared to David’s psalms and Augustine’s Confessions, many being meditations on the psalms, and expressing ‘sighs of the heart’. Suffering a terminal illness, Gregory is highly personal in his pastoral prayers. He reminds us that people have been the same all through the centuries, and that God can still be approached in the same way seekers have sought his presence since the early church.

Another stream strongly influenced by the Coptic tradition was Celtic spirituality which has enjoyed a revival over the past few decades. As I have written earlier, the influence of the eastern origins of Celtic monastic life can be found in monastic rules, the beehive architecture of monks’ cells, the round towers and layout of monastic communities and some Celtic manuscript illuminations are clearly copied from Coptic sources.

Ray Simpson, Andy Raine and Philip Newell are some of those who have developed meditation and worship resources based on Celtic spirituality. Features of this spirituality included a strong awareness of God’s presence in his creation; an emphasis on community lifestyle lived daily, that people and relationship mattered more than things and reputation; that women and men were equal in God’s kingdom and shared in leadership giftings; that contemplation and prayer on the one hand belonged together with action and engagement on the other.

St Benedict is another voice from the first millennium still heard by multitudes today through Lectio Divina, divine reading. While Origen developed Scriptural reflection and interpretation as early as the third century, influencing other church fathers like Ambrose and Augustine, it was Benedict in the sixth century who formalised a particular way of meditation for the monks of the order he established, which became the standard for western monasticism.

The four basic steps of the Benedictine practice were formulated by Guigo II in the twelfth century as: Lectio (read), Meditatio (meditate), Oratio (pray) and Contemplatio (contemplate). Scripture was not approached as a text to be studied but as feasting on the Living Word. Taking a bite (lectio) led to chewing (meditatio), followed by savouring its essence (oratio) and lastly digesting it (contemplatio).

The Modern Devotion movement emerged in the Netherlands during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries bringing spiritual renewal in response to the arid scholasticism of the day. The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, originating in Deventer and Zwolle, became hugely influential among monasteries across northern Europe. Thomas a Kempis’ classic The Imitation of Christ became the most widely-read devotional book in western Christian history. Essentially it was the discipleship manual of the movement, still relevant for us today despite clear pre-Reformation features.

Luther’s Breviary encourages the reader to follow the liturgical year, day-for-day with a verse from the Bible and Martin Luther’s interpretation of it. The Pietistic movement of the seventeenth and eighteenth century brought a renewal of personal devotion into mainstream Lutheranism, and in 1728 the Moravian movement started producing daily texts known as Losungen (Watchwords), used today in sixty-two languages around the world.

We finished our week reading the daily prayer for August 2 from the Common Prayer book, a contemporary compilation from many wells of history, stressing the ‘we’ rather than ‘me’ in worship and devotion. Highly commended!

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

For more weekly words from Jeff, visit weeklyword.eu.

This Post Has 0 Comments