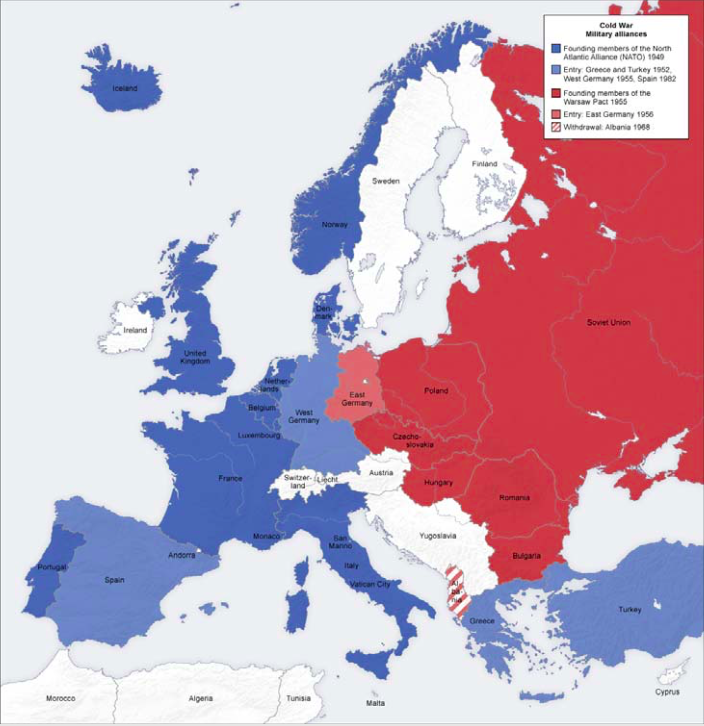

Europe: the last 25 years

This year Europe commemorates the 30 years of a series of events that led to the end of the Cold War. On this occasion, the Schuman Centre publishes an article from a special edition of Vista Magazine in the occasion of the 25 years of the end of the Cold War five years ago (see Vista edition 19)

During the early 80s, as I became more aware of world and regional politics, European politics was dominated by that apparently impregnable wall separating East from West and of the vast empire of the USSR whose ranks were massed behind it. Our home received, as did many other homes of the era, a booklet outlining what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. I remember reading that I should shelter under the stairs and put a bucket over my head (or something to that effect).

Then Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union in 1985 and attempted to decrease tensions with the west and introduce political liberalisations in the USSR. As communist governments crumbled during 1989 and the reunification of Germany in 1990 became inevitable, the Cold War finally spluttered to a halt. I shared the amazement, disbelief, and joy of many as we watched on our TV sets the Berlin Wall being physically dismantled.

I’ve now lived half of my lifetime in the wake of the political, economic, social, and religious changes ushered in by the events of the late 80s and early 90s. Many of those have been beneficial and welcome changes.

However, the economic and political crisis of the twenty-first century’s opening decade prompts the need for a fresh evaluation of the role of Christian faith and the contribution that the good news about Jesus Christ can make to contemporary Europe. Here I want to highlight some significant developments of the last quarter of a century and review some ecclesial and missionary developments during that period.

Nationhood, independence and ethnicity

Armed conflict ravaged former Yugoslavia for the eight year period 1991-1999, resulting in some 140, 000 deaths and massive loss of infrastructure. Competing nationalist aspirations and ethnic tensions fed these wars. Although armed hostilities in the Balkans finally ceased with the ending of the Kosovo War in 1999, regional tensions remain.

As the European Union extended its borders with the accession of new member states in 2004, 2007, and 2013, the countries of the EU have been forced to face the realities of increasingly diverse populations. This continues to fuel ethnic and nationalist tensions which drive Euro-sceptical movements and political parties, lend support to forms of political extremism targeted at ethnic minorities, and which become increasingly resistant to particular groups of immigrants.

Of course the aspiration to nationhood and self-determination is not always malignant and, in the case of Slovakia and the Czech Republic, saw the ‘Velvet Divorce’ between the constituent territories of the former Czechoslovakia. In the case of Scotland it generated sufficient momentum towards a referendum on independence in 2014 (unsuccessful) and continues to stir the desire for independence in Catalonia and other regions of Spain, moves consistently resisted by the Spanish Federal Government.

New forms of political alliance

With the expansions of 2004, 2007 and 2013, the EU went from a membership of fifteen to twenty-eight. Eleven of these new member states were under the hegemony of the USSR twenty-five years previous. A further four former Soviet-bloc territories are either formal candidate countries or have potential candidate status (Albania, Macedonia, Bosnia- Herzegovina, and Kosovo) and two (Montenegro and Serbia) are negotiating a roadmap towards accession.

The former USSR was replaced by a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) headed by the Russian Federation and through which it promotes its interest in maintaining close ties with ethnic Russians or Russian-speaking passport holders in what it frequently refers to as its ‘near abroad’. The presence of ethnic Russians in Georgia and Ukraine lent justification for Moscow’s claims of protecting Russians living in Ukrainian territory in Crimea and its control of former Georgian territory in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Moldova is also vulnerable in this regard, having its own ethnic Russian population in the Transnistria region, east of the Dniester River and bordering Ukraine. Whilst the three Baltic states also have ethnic Russian populations they are afforded the relative protection of NATO membership.

Increasing cultural and religious diversity

Citizens of a majority of EU states, have the right to travel, reside, work, and conduct business in any of the EU’s member states. However, this has come at the expense of stricter external border controls for some. Migrants seeking refuge and asylum experience this on a daily basis as they try to enter the EU without proper documentation.

The presence of documented and undocumented immigrants in Europe has accelerated its cultural and religious diversity and prompted new policy and political responses. During the mid- ‘noughties’, European politicians began to announce the demise of multiculturalism. Accompanying this was a new focus on ‘interculturalism’ that promoted a more intentional approach to the integration of migrants through policies supporting language acquisition, entry in education and the workforce, and the promotion of national or European values (assessed formally in some countries).

With cultural diversity came religious diversity and an increasing European sensitivity towards Islam in its more radical forms. The secular 1970s did not prepare Europe well for the religious vitality that would become all too apparent during the late 1990s and onwards. Religious conviction was implicit in the various Balkans conflicts with, for example, Serbian Orthodox fighting against Bosnian Muslims and Croatian Catholics. The use of religious labels is unconvincing to most theologians or religious teachers but their adoption by various movements has been remarkable in creating and sustaining committed identity and purpose, especially where these are directed towards the pursuit of violence.

Church and Mission in Europe

Over the last twenty-five years I have noticed a careful re-assessment of the evangelical euphoria that was apparent during the early 1990s in Central and Eastern Europe. It seemed than that the call to conversion was “Repent, believe, be baptised, and take a truckload of Bibles, children’s clothes, etc. to Romania!” These early years saw an unprecedented openness to the Gospel, new religious freedoms, and a plethora of church planting ministries, Bible and literature distribution, social ministries, and evangelistic initiatives. This was bolstered by the arrival of large numbers of missionaries from US, Korea, and various western European mission agencies. Effective partnerships led to the establishing of many more local evangelical congregations in parts of Europe.

However , the presence of missionaries was not without its tensions. Their presence was resented almost unanimously by the traditional churches (Orthodox and Catholic) and not infrequently by existing evangelical churches which experienced the loss of formerly active members to non-indigenous churches that were well-funded and well- resourced from the west.

The missionary activity of recent years has become more sensitive to the local context. Church planting from the west has lost the appeal of its novelty. Sustained and longer- term approaches are seen to be more appropriate. There are also, for example, innovative examples of evangelical co- operation with traditional churches, notably from among mission societies such as the British CMS or the German EMW and agencies such as World Vision.

In taking seriously their missionary commitment to Europe, there are also Christian churches and individuals who understand the need to engage their Christian worldview with the largely secular corridors of political, economic, cultural, social, and educational power . The European Union is now required to serve and reflect the interests of twenty-eight countries. Many of these are much more ‘non-secular’ than the pre-2004 ‘club of fifteen’. Engaging with European institutions will not, however , be unproblematic for people of faith but it does at least open up the possibility of a new way of re-introducing the people of Europe to a convincing and compelling account of the Christian faith and the witness it give to the good news of Jesus.

Darrell Jackson

Associate Professor of Missiology, Morling College. darrellj@morling.edu.au

This Post Has 0 Comments