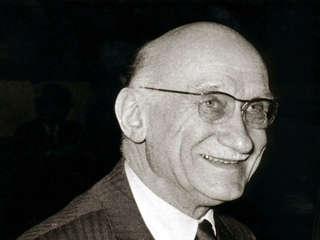

The arrest and escape of Schuman (Part IV)

From Jeff Fountain’s book Deeply Rooted (Part I here, Part II here, Part III here)

Through his underground connections, he arranged for false papers in the name of Monsieur Durenne (inspired by his mother’s name). On August 1, 1942, taking advantage of the relaxed guard, he slipped away unnoticed. Knowing the region well, and with many friends and contacts, he found shelter in convents and monasteries, travelling by foot through forest tracks towards Free France.

As he expected, a massive manhunt was launched immediately to track him down in the Rhineland, throughout Alsace and Lorraine, and in occupied France. A reward of 100,000 Reichsmarks was offered for his arrest.

Thirteen days, seven hundred kilometres and several narrow escapes later, ‘Cordonnier‘ safely crossed the demarcation line into Free France at Montmorillon, east of Poitiers.

He pressed on to Ligugé, just south of Poitiers, to call on the abbot of St Martin’s, Dom Basset, to deliver his shocking message of the systematic destruction of the Jews.

Dom Basset recorded the conversation himself as follows: There are no more Jews in the Ukraine. Men, women and children have been separated and taken. Men and women have been transported to concentration camps. Often they are sent with hardly any water and without food. They are left to die of starvation and cold. They are often made to dig huge trenches and they are then shot in front of them. They are set on fire with petrol, then covered in lime and earth. The Polish Jews are often destroyed by such radical methods. They are transported, separating father, mothers and children. When the German populations are transported, the families are transferred. The same goes also for those from Alsace-Lorraine. But they had to leave without taking practically anything with them, leaving their country, and finding themselves in very difficult conditions.

Basset was probably the first person in the free world to hear news about the holocaust from a reliable source. As suggested, Schuman may have gleaned some of this information directly from high Nazi officials.

Schuman moved on to Vichy. He felt a duty to tell Pétain himself what he knew, whether or not he would listen. Pétain had wanted Schuman to serve in his government and Schuman had refused. Would Pétain be prepared to listen to him now? Even if he would not, the Allied powers had set up embassies at Vichy after the move south from Paris and they needed to hear.

It took Schuman all his persuasive powers to penetrate the inner circles protecting Pétain. At last he was able to catch him at a dinner for a few minutes and report about the destruction of Jews.

Pétain remained stoney-faced and unmoved. After all, among his first decrees the marshall himself had excluded Jews from government, and from the liberal professions such as medicine and law.

Among the public, however, news of Schuman’s escape created great excitement, especially for the refugees from Alsace-Lorraine. Schuman addressed public meetings attended by up to 1500. He had news that was ‘grave, full of hope, deep and spiritual’. His message that Allied victory was just a matter of time boosted morale greatly. Germany was certain to lose the war, he told attentive crowds in Lyon and other centres. His listeners heard how that his imprisonment had enabled him to investigate Germany’s enormous losses on the eastern front, and gather specific numbers and details. The war was not sustainable. Sooner or later, Germany would have to capitulate.

He also described the Nazi enslavement of Germans as well as other peoples. Yet records of these meetings are not clear how much if anything Schuman said publically about the Jewish extermination.

He met up with many old colleagues and trusted friends, and most certainly would have shared with them what he had told Dom Basset, a virtual stranger.

Schuman had made his escape none too soon. The comparative freedom of the Vichy territory was to be short-lived, for within weeks the Germans invaded the unoccupied rump of France. Now the SS were free to search more intensively.

De Gaulle (a fellow undersecretary in the Reynaud government) invited Schuman to join him in the government-in-exile in London. Instead, he elected to stay in France, secluded in the orphange of La Providence de Beaupont in Bourg-en-Bresse. Yet his enforced withdrawal from public life gave him opportunity to reflect, research and plan for the reconstruction of Europe once the expected end arrived.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

This Post Has 0 Comments