Making war impossible – the story of Schuman (part III)

From Jeff Fountain’s book Deeply Rooted (part I here – part II here)

Monday morning, May 1, as the train pulled into Gare de L’Est, Clappier stood on the platform anxiously waiting for his boss. Schuman stepped down from the carriage, greeted hischef de cabinet, and without further word walked towards the waiting car. On the drive to the Quay d’Orsay, Clappier was bursting with curiosity, but Schuman insisted on talking only about the weather.

Finally Clappier put the question directly: “Monsieur le ministre, the paper I gave you last Friday, what do you think about it?”

“I’ve read the proposal. I’ll use it,” Schuman told him with deliberate understatement.

Clappier knew immediately the following days would be a whirlwind of planning and preparations, drafting and redrafting. He also understood discretion would be crucial to success. Only the right people should know, to avoid any efforts to thwart the plan.

Schuman and Monnet informed a sceptical prime minister, and two other ministers known for their belief in ‘Europe’. A meeting of the French cabinet was arranged for May 9, the day before the Big Three meeting in London.

The following Monday, May 8, Schuman briefed a trusted official, Robert Mischlich, to undertake a ‘delicate and secret mission’, to deliver letters to Adenauer in Bonn outlining the secret plan.

The next day, the French cabinet was coming to the end of its agenda. Schuman had remained silent about his proposal throughout the meeting, waiting to hear back from Bonn. Finally Clappier slipped him a note saying that Mischlich had relayed Adenauer’s enthusiastic response: ‘This French proposal is in every way historic: it restores my country’s dignity and is the cornerstone for uniting Europe.’

With this information, the foreign minister asked to raise an urgent new agenda item. He then tabled the plan and the report of Bonn’s agreement. The two ministers in the know immediately voiced their support. Others, caught off guard by the boldness of the plan, needed more convincing. Hesitatingly, and despite some private reservations, the cabinet eventually agreed for the proposal to be presented at a press conference at six o’clock that evening, at Quai d’Orsay, the seat of the Foreign Ministry.

Prepared texts were hurriedly delivered to the ambassadors of Italy, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Britain and the United States. Invitations went out to two hundred journalists.

However, by six that evening, only a handful of Paris-based journalists were free, at such short notice, to join the government officials, politicians and diplomats gathered under the high ceilings, chandeliers and gold-painted baroque decorations of the grandiose Salon de l’Horloge.

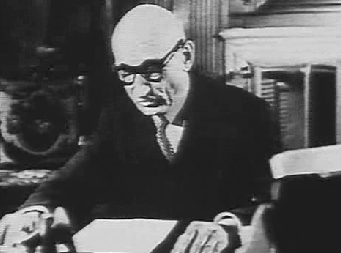

Schuman stood before an enormous mantlepiece with Monnet seated at his side as he called for order. The audience hushed as he sat down and began to read through his heavy horn-rimmed glasses.

World peace, he began, required creative efforts of equal magnitude to the threats. French efforts to champion a united Europe in the past had failed, and war had resulted. Yet such a united Europe would not happen at once. It required steps that would build solidarity, and eliminate the age-old enmity of France and Germany.

Therefore, he read, his government would propose specific, concrete action on one decisive issue: that French-German production of coal and steel be pooled under a common High Authority, above the authority of the national governments, and open for other European countries to join.

This would encourage common foundations for economic development, and would change the destinies of those regions which historically had been devoted to the production of war munitions, and which had been the most constant victims. Here Schuman was referring primarily to the Saar and Ruhr industrial regions.

This solidarity in production would make war between France and Germany not just unthinkable, but materially impossible.

Schuman looked up from prepared statement on the table in front of him, taking in the rows of expectant faces hanging on his every word. The boldness and the far-reaching consequences of this proposal was lost on no-one in the room. All that could be heard, as everyone waited for the foreign minister to continue, was the sound of the stenographer seated directly in front of him, capturing every word on her large mechanical typewriter.

This unity of production, he resumed reading, would lay a true foundation for the economic unification of all countries willing to take part. It would contribute to raising living standards and promoting peaceful achievements. Europe would then be able to focus on one of its essential tasks, the development of the African continent.

A common economic system would emerge from such cooperation, leading to deeper community ties between countries often opposed to each other.

The establishment of such a High Authority whose decisions would bind France, Germany and other members nations would lead towards a European federation necessary for sustained peace, he concluded.

A momentary pause signalled the enormity of what had just been proposed, before the journalists rushed out the doors to their newsrooms.

Jeff Fountain

Director Schuman Centre

This Post Has 0 Comments