Canaries in the coal mine

Following the killings of four Jews in a kosher market in Paris last month, commemorations held last week of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp by Soviet troops carried special poignancy.

Following the killings of four Jews in a kosher market in Paris last month, commemorations held last week of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp by Soviet troops carried special poignancy.

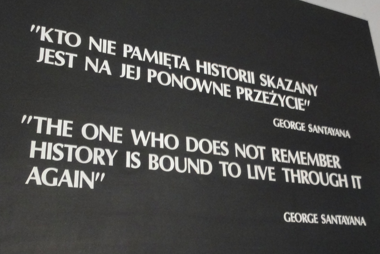

As a handful of aging camp survivors revisited the scene of one of the greatest crimes in history–where 880,000 Jews were ruthlessly exterminated–they must have been disturbed by the familiar quote from George Santayana displayed on a barrack wall: ‘The one who does not remember history is bound to live through it again.’

For, as Lord Jonathan Sacks has been warning recently, ‘Never again’ has become ever again. In a Wall Street Journal article published last October, Rabbi Sacks described an apprehension he had not known in his lifetime about the return of anti-Semitism to Europe within living memory of the Holocaust.

This should concern all Europeans, he wrote, not just Jews. For the politics of hate that began with Jews never ended with Jews. Anti-Semitism was the early warning signal of a society in danger.

‘Jews are the canaries in the coal mine,’ explained Warren Goldstein, Chief Rabbi of South Africa, in the Jerusalem Post following the recent Paris attacks: ‘If the Jews in a particular society are, like the canaries, singing and thriving then all is well. If not, that is an early warning of danger ahead. The world ought to rely on the position of Jews to assess the threat level to civilized society.’

Future in Europe?

Lord Sacks chronicled events from the past year to underscore his apprehension: ‘In France, worshippers in a synagogue were surrounded by a howling mob claiming to protest Israeli policy. In Brussels, four people were murdered in the Jewish museum, and a synagogue was firebombed. In London, a major supermarket said that it felt forced to remove kosher food from its shelves for fear that it would incite a riot. A London theatre refused to stage a Jewish film festival because the event had received a small grant from the Israeli embassy.’

And that was before the last attack in Paris.

Well-established British Jews had told Rabbi Sacks that for the first time in their lives, they felt afraid. One in three of Europe’s Jews had considered emigrating because of anti-Semitism, he wrote, close to half of those in France and in Hungary. Many Jews were quietly asking if they had a future in Europe.

Goldstein saw the savage killings at Charlie Hebdo and of Jews in the kosher supermarket as profoundly connected. A society in which Jews were not safe would ultimately not be safe for journalists, or for freedom, or for any values of human decency. If Jews were not safe in France, he stressed, then the very future of France was in jeopardy, and so indeed was the future of the civilized world. The many attacks on French Jewry were all early warning signs of the lethal threat posed by radical Islam.

Sacks acknowledged that Europe today was not Germany in the 1930s, citing recent denunciations of anti-Semitism from Angela Merkel in Germany and David Cameron in Britain. Yet he believed what was happening was nonetheless immensely significant. Anti-Semitism had always been only obliquely about Jews. They were its victims, not its cause. Jews did not suffer alone under Hitler and Stalin. Jews were not alone in suffering today under their successors, radical Islamists.

Politics of hate

Christians and other minority faiths in the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia were also being attacked. Ultimately, Western democratic freedoms were under attack. Europe itself would be pushed back toward the Dark Ages if the attack was not halted, he warned.

Historically, anti-Semitism had always been the inability to make space for differences among people, wrote Sacks, which was the essential foundation of a free society. That was why the politics of hate now assaulted Christians, Bahai, Yazidis and many others, including Muslims on the wrong side of the Sunni/Shia divide, as well as Jews. To fight it, we had to stand together, concluded Sacks, people of all faiths and of none. The future of freedom was at stake, and would be the defining battle of the 21st century.

Goldstein also called for a global alliance of people from across all faiths and countries to defend human civilization from Jihadi barbarism. Just before and after the Paris attacks, two thousand people were butchered by Boko Haram; then ten-year-old girls were sent as suicide bombers to attack markets in Potiskum, Nigeria; and barbarians butchered more than two hundred children in Peshawar, Pakistan. These attacks, he wrote, constituted the dire danger and sickness of a brutal and savage movement that threatened all civilised decent people throughout the world.

Never again?

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments