Old and New

These days between Christmas and New Year offer time to reflect on reading material which influenced my thinking over the past twelve months, books both old and new.

These days between Christmas and New Year offer time to reflect on reading material which influenced my thinking over the past twelve months, books both old and new.

The oldest of course is the Bible itself, which continues to amaze me as the life-source of so much we take for granted in our western world. For just a few days ago, Monsignor Piotr Mazurkiewicz, my colleague at a Timisoara University seminar we addressed together, explained how western democracy did not develop from Athenian ‘democracy’, which assumed a social base of slavery, but from a biblical view of humanity. Human beings reflecting God’s image demanded respect from governments, institutions and individuals, he said.

The influence of Biblical revelation can even be found in Far Eastern cultures, according to a book I was introduced to at the Mission-Net Congress in Germany exactly a year ago this week, Finding God in Ancient China. Former TIME correspondent in Beijing, David Aikman, commends author Chan Kei Thong for demonstrating ‘that Chinese classical literature is entirely consistent with Christian revelation’. An eye-opener for me, this book reveals how the ancient Chinese worshipped a monotheistic God whom they called Shang Di.

All-time favourite with a growing global readership, Tom Wright continues to offer fresh perspectives on the biblical narrative. His 2012 title, How God became King, exposes how the heart of the gospel is often missed in preaching, ancient and modern. The Nicene Creed, for example, leaps from the Incarnation to the Crucifixion, leaving out the ‘missing middle’, the message of God’s kingdom. Wright boldly claims that the Western church has missed the point of the gospels and suggests steps for recovery.

Aftermath

Another personal favourite on Biblical themes, although not Christian, is Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, whose 2011 title, The Great Partnership, I picked up at Yorkminster Cathedral last summer during our Celtic Heritage Tour. Science and religion are complementary, not mutually exclusive, the rabbi argues. Both are necessary for understanding the human condition: science takes things apart to see how they work; religion puts things together to see what they mean. When a society loses its soul, he warns, it will soon lose its future.

Few books have addressed the aftermath of World War Two. Ian Buruma, in Year Zero–a history of 1945, recreates the trauma, the revenge, the regrets, the cruelties, the despair, the hopes and the realities of post-war Europe and Asia when lives, families, cities and nations had to be rebuilt. For both the boomer generation and their children, this is an arresting account of the birth-pangs of our post-war era of peace and prosperity we have tended to take for granted–until the events of this year.

Those events, starting with Putin’s invasion of Crimea shortly after ‘his’ Sochi Winter Olympics, the tragedy of flight MH17, and culminating in the rouble’s fall, had me reaching for several books of the shelf. I read passages from The New Cold War (2008) to my wife in which Edward Lucas warned that Russia was reverting to behaviour last seen during the Soviet era. Authoritarian, bureaucratic capitalism, bolstered by natural resources, effective secret police and stifled media, had taken root. The 1990’s were over, he wrote. It was high time to treat Russia as the authoritarian regime that it was: like China or Kazakhstan.

I also read my wife other prescient passages from George Friedman’s 2009 book, The next 100 years. For example: ‘The reabsorption of Belarus and Ukraine into the Russian sphere of influence is a given in the next five years’.

Collapse

This year also marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the dramatic collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, as we have focused on in several recent weekly words. More old titles came down off the shelf, while others were found for a pittance on the web, to recall the stories behind yesterday’s headlines and trace the spiritual roots of the people’s revolution from country to country.

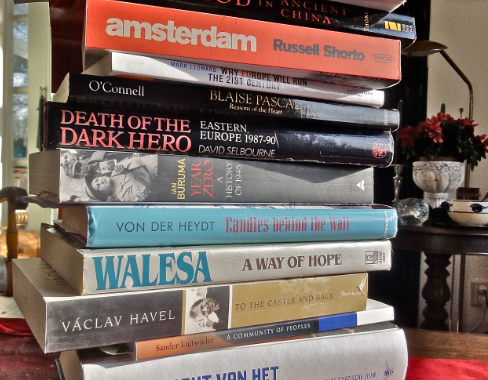

These titles included To the castle and back (2008), Vaclev Havel’s stirring tale about the prisoner-poet who became president; Lech Walesa’s A way of hope (1987), written before the shipyard electrician also was imprisoned en route to becoming president; Death of the dark hero (1990), an eye-witness account by a disillusioned leftist British academic David Selbourne as he traversed Central and Eastern Europe observing the unravelling of the old order. Both Candles behind the Wall (1993), [Barbara Von Der Heydt], and The Final Revolution (2003), [George Weigel], reveal the spiritual roots of this great upheaval.

Where will this all lead? Mark Leonard argues in Why Europe will run the 21st century (2005) that the European model of a values-based community will continue to shape the ‘Eurosphere’ of over 100 nations. De kracht van het paradijs (2014) is Jonathan Holslag’s visionary view on how Europe is to survive in an Asian century. Finally, Sander Luitwieler in A community of peoples (2014) offers a via media between federalisation and decentralisation, stressing how the values of freedom, peace, equality, community and diversity require a biblical anthropology for sustainability… bringing us full circle back to the Bible.

Till next year,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments