Democracy and its dissidents

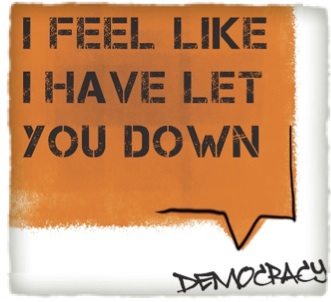

The decor on the platform depicted the grey concrete of the Berlin wall. Graffiti slogans spoke on behalf of ‘democracy’: ‘I miss how loved I was 25 years ago’; ‘I feel I have let you down’…

The decor on the platform depicted the grey concrete of the Berlin wall. Graffiti slogans spoke on behalf of ‘democracy’: ‘I miss how loved I was 25 years ago’; ‘I feel I have let you down’…

The setting was Zofin Palace on an island in the Vlata River flowing through picturesque Prague. The occasion was the annual Forum 2000 held last week, pursuing the legacy of Václav Havel in support of the values of democracy, respect for human rights and civil society. Havel, the Czech dissident who became president, played a key role in the Velvet Revolution which overthrew communistic tyranny a quarter century ago. The Cold War system was collapsing and new democracies were springing up across Central and Eastern Europe. The atmosphere was euphoric with high hopes and expectations about the freedoms democracy would bring.

Yet Havel was under no illusions about the fragility of democracy. As early as 1971 he had written: ‘The natural disadvantage of democracy is that it binds the hands of those who take it seriously while allowing those who don’t take it seriously to do almost anything they want.’

Havel first initiated the forum 18 years ago to discuss the challenges facing humanity on the threshold of the new millennium.

Twenty-five years after the democratic revolutions, many are worried about the current state of democracy. The failed hopes of the Arab Spring, Russian intervention in the Ukraine, the international community’s half-hearted response to it, the rise of European extremism and populism, increasing global infuence of the communist regime in Beijing, the challenge of Islamic fundamentalism not only in the Middle East but within our western cities, and the increasing global economic inequality, all has put the democratic world on the defensive.

Respect

What type of democracy do we have today? Why is there so much distrust of politicians and political institutions? Why are voting turn-outs so low? These questions reflect the concerns Havel had about the quality of democracy today and its future. Some four thousand participants, including 200 global leaders from politics, academia, civil society, media, business and religion, had convened in Prague to address these questions.

Havel, who died nearly three years ago, recognised that truth and love had transcendental origins. If democracy was not only to survive but to expand successfully, he said, it had to ‘renew its respect for that non-material order which is not only above us but also in us and among us and which is the only possible and reliable source of man’s respect for himself, for others, for the order of nature, for the order of humanity, and thus for secular authority as well.

‘The loss of this respect always leads to loss of respect for everything else–from the laws people have made for themselves, to the life of our neighbours and of our living planet. The relativisation of all moral norms, the crisis of authority, reduction of life to the pursuit of immediate material gain without regard for its general consequences–the very things Western Democracy is most criticised for–does not originate in democracy but in that which modern man has lost: his transcendent anchor and along with it the only genuine source of his responsibility and self-respect.’

Unwanted child

The role of Christianity in shaping democracy and human values was clearly stated in several sessions I attended. Tomas Halik, professor of philosophy at Charles University, described liberal democracy as ‘the unwanted child of the church’. The space between throne and altar in western Europe had allowed civil society to emerge; the Reformation had been an attempt to democratize the church; the Enlightenment and secularisation had resulted from the disappointment in the church shared by Christian intellectuals. Yet Christian values had remained deeply embedded in secularised society, he added.

A German panel member explained that democracy had no intrinsic truth and could not make values, but lived from people who had their own values. In Communist East Germany, the church had been the only space outside the state for independent thought and education. All opposition had gathered under the roof of the church. All democratic values had been promoted through the church. For the church had carried an important message: obedience to God came first.

The implications of the views of several contributors carried clear warnings for a secularised Europe: while Christianity and liberal democracy were closely related as both were about human beings, without faith democracy could not be sustained. Which echoed Robert Schuman’s belief that democracy had to be rooted in Christianity or it would become either tyranny or anarchy.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments