Lest we forget

This month we entered a four-year season of remembrance and commemoration. Through a barrage of television documentaries and newspaper articles, we will be reminded of the battles of World War One: Verdun, the Somme, Ypres, Gallipoli, Jutland and many more. We will soon re-live the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the birth of the Soviet era.

All this will lead to reflection on the vengeful Treaty of Versailles which sowed the seeds for the next global war, which in turn was followed by a cold war and eventually the end of the Soviet era.

We had thought that fearful era was safely behind us when, just a few short months ago, events in the Crimea reminded us that human nature hasn’t really changed.

Parallels and comparisons with Europe a century ago are already beginning to fill pages in papers, magazines and websites. Harvard historian Niall Ferguson warned in the Financial Times a few days ago that ‘the guns of August 1914 ended the era of European predominance with a deafening bang’, and asked: Could such a catastrophe recur in our time?

Ferguson sees alarming similarities in the Ukraine crisis since the downing of MH17 to the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 in Sarajevo: both were acts of state-sponsored terrorism. Now, as then, ownership of a seemingly unimportant region of eastern Europe is disputed. Now, as then, the situation is escalating with Russian forces building on the Ukrainian border. Then, no-one expected that ‘small crisis’ to lead to all-out war. All it took, argues Ferguson, was a series of blunders by Europe’s leaders. He warns against the blunder of cornering a desperate, unpredictable and ambitious man like Putin.

Differences

No doubt many more parallels and comparisions will be drawn in the months and years ahead. Both similarities and differences will help inform our reflection on the current state of Europe.

One clear difference is our attitude to war. If war were to break out among Europe’s major powers today, there would be no scenes of public euphoria with flag-waving, jingoistic war-chants and patriotic singing of national anthems, as happened in Berlin, London and Paris a hundred years ago this summer. Everyone would be deeply aware that a great tragedy had come upon us all.

Most young Europeans today have grown up with the unconscious assumption that war among European nations was impossible, a thing of the past. That thought itself was considered impossible in the immediate post-war years until the European project of ‘ever-closer union’ began to take root.

Closely allied to this is the change in attitude towards nationalism. We grimace when we read how European nations demonised their enemies. We cringe when we read how nations claimed God was exclusively on their side: on the one side, buckles with Gott mit uns; on the other, slogans of For God and King.

And yet we see worrying signs of renewed nationalistic fervour promoted by populist politicians oblivious to the great lesson of the twentieth century, that the foundations for Europe’s future had to be laid through forgiveness and reconciliation.

The role of the Bible and Christianity in Europe a century ago compared to today underscores what Dr Evert van de Poll asserted during our Masterclass in European Studies in Geneva: paradoxically, Europe is the continent most influenced by the Bible and at the same time by its rejection.

Respect

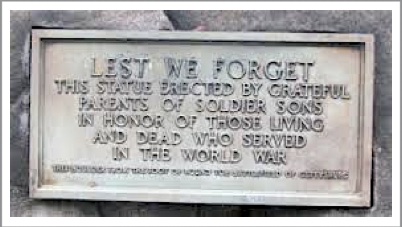

The Bible was used both to justify and to condemn the war on both sides. Millions of Bibles were issued to soldiers of both sides. Soldiers in opposing trenches sought consolation from their Bibles in lulls between fighting. While Biblical literacy made not have been widespread, respect for God’s Word was. War memorials erected in towns and villages across Europe and throughout the British Commonwealth often quoted Bible verses, a favourite being, ‘Greater love hath no man than this that he lay down his life for his friends’ (John 15:13).

The most common inscription on British Commonwealth memorials–‘Lest we forget’–is from a hymn by Rudyard Kipling, God of our fathers, we used to sing at my grammar school on ANZAC Day. Actually, it is not about remembering the fallen, important as that is. It is a prayer to God for mercy on Britain and her dominions, that they would not forget their God and lapse from the Christian faith:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget–lest we forget!

Sadly, compared with a hundred years ago, this is a prayer we have largely forgotten.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments