Woven strands

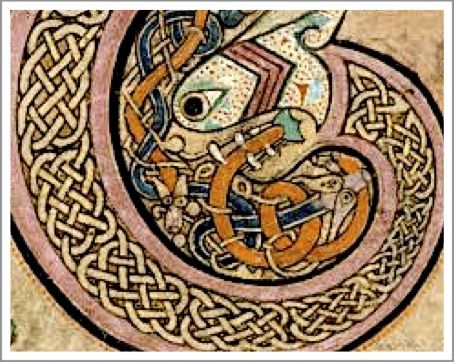

The Book of Kells, on permanent display in the Trinity College Library in Dublin, weaves the strands of Coptic, Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Roman Christian traditions together into a tapestry depicting a dynamic, creative, artistic, life-affirming, creation-loving, relational and Christ-centred movement with much to teach us still today.

Starting our Celtic Heritage Tour in Dublin, to follow the progress of the gospel across to Scotland and down into England over 1400 years ago, we are tracing the story of the transformation of tribes, clans and peoples through the message of love, reconciliation and brotherhood which laid the foundations of Irish and British socieities and cultures.

This rich heritage of the Celtic saints inspires us to acknowledge what God has done through faithful individuals and creative minorities in the past, and thus what he can do again today. It offers landmarks to guide us in both our personal spiritual journey and our corporate pilgrimage towards unity as a Body of Christ made up of many traditions. And it beckons us to learn from these ancient ‘teachers of nations and disciplers of kings’ about presenting the Christian way of life to today’s spiritual seekers.

Monastic cities

Our journey so far has taken us to the sites of former monastic communities, each founded by an Irish saint: Glendalough (Kevin), Kildare (Brigid), Clonard (Finnian), Durrow and Kells (Columba), Clonmacnoise (Ciaran), and Clonfert (Brendon).

These were not just small cloisters with a handful of few monks, but were called ‘monastic cities’ with up to 3000 inhabitants clustered in round wattle huts. Neither were they short-lived idealistic communities such as the hippie communes of the 60’s and 70’s. Founded in the mid-sixth century, some of them lasted a thousand years until Henry VIII decreed the dissolution of all monasteries in the British Isles.

From their rhythm of prayer, work and recreation emerged a lifestyle that interlaced the elements of simplicity, worship, purity, obedience, of care for creation, of bible study and scholarship, of unity with diversity and of mission.

The Celtic Church regarded the Apostle John as its spiritual father. The evangelist is often symbolised by the eagle, the only creature able to look straight into the sun and not be dazzled. John, the Celts understood, gazed into the eternal secrets of of heart of God. Of the four gospels writers, John alone describes Christ as creator and sustainer of the universe, the light of every person who comes into the world. John in his letters stressed that God was love. The Celts emphasised a relational Christianity rather than one of rules and hierarchy.

Ray Simpson of the Community of Aidan and Hilda has written extensively about the common threads of Celtic spirituality. Firstly, he writes, Celtic believers thought of themselves as belonging to one universal Church. They believed in a common doctrine as expressed in the Apostles’ Creed. They accepted the same Bible, as approved by the one universal Church. They looked to connect with church leaders in other lands, conscious of their own roots via Patrick with the church in Gaul, where Irenaeus, disciple of Polycarp, disciple of John, had lived for over two decades.

Broken cord

Hence the various strands woven together in the beautiful pages of the Book of Kells, reflecting the respect and honour given to different traditions within the universal church. For us today, denominationalism is normal. But for the Celts, there was only one Church, even if differences had begun to emerge. The Great Schism only occurred in the second millennium. The Reformation which followed in the sixteenth century may have recovered some biblical truths, but it also lost vital insights.

We cannot undo history, writes Simpson, but ‘through a weaving together of the different strands of spirituality we can restore the “Christian cord” which has been broken. Through making common cause with other Christians in witness and work for a just world we can move beyond the tramlines of the past.’ (see ‘ A Pilgrim Way’, p.122)

The Way of Life, he says, calls us to weave together what is God-given in Christianity’s strands, however great their failings. It calls us to be open to learn from different streams, whether they be the expository, sacramental, contemplative, justice or charismatic streams.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments