Making history in the Crimea

Clearing out some drawers last week I came across a couple of old maps of the Crimea picked up on various visits to the peninsular over the past two decades.

On one visit, I arrived in Simferopol after 19 hours on a Soviet-era train from Rostov-on-Don in Russia. Yalta was my destination, which I finally reached after a further journey on the world’s longest trolley bus route, nearly 100 kilometres long.

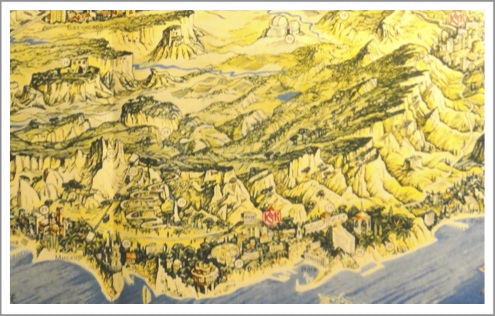

Like an illustration from Lord of the Rings, one map showed relief sketchings of the Crimean Mountains along the southern Black Sea coastline, rising from the sea with spectacular fortress-like cliffs to a height of 750 metres. Resembling a diamond-shaped wedge of cheese, the whole peninsular slopes gently from the clifftops towards the northern corner where it is attached to the mainland by a narrow isthmus.

Even before the Greeks settled here along the sun-facing coast, the Scythians, mentioned in the Bible, left numerous ancient burial mounds across the Crimean steppes. Goths, Huns, Byzantine Greeks, Venetians, Genoans, Ottoman Turks, Tatars and Mongols have all taken turns settling on the peninsular. The name Crimea itself comes from the Tatar word qirim for ‘steppe, hill’.

A Tatar state was set up by a descendant of the Genghis Khan in 1441 and lasted until 1783 when annexed by the Russian Empire. The Tatars raided Slavic settlements to the north taking captives and selling some two million slaves on to the Ottoman Empire.

Protector

The entire Crimean population of the Tatars themselves were forcibly deported by Stalin to Central Asia as punishment for collaboration with the Nazis in May 1944. Nearly half died from hunger and disease. Next the Armenian, Bulgarian, and Greek populations were also deported to Central Asia, so that by the end of summer of 1944, the Crimea had been ethnically cleansed. Ethnic Russians have since formed the large majority of the population, despite the return of Tatars from Central Asia since the end of the Soviet Union.

One of the first modern wars using technologies like railways and telegraph was the Crimean War of 1853-56. Florence Nightingale emerged during that war as a heroine, pioneering new medical practices while treating wounded British soldiers and earning recognition as mother of the modern nursing profession. The war was an effort by Britain and France to stop Russia expanding at the expense of a declining Ottoman Empire. Russia saw her role as the protector of Orthodox believers living under Ottoman control, including in the Holy Land, echoing Russia’s present claim to protect the interests of ethnic Russians outside her own borders.

Tsar Nicholas wrongly calculated he could get away with the annexation of a few neighbouring Ottoman provinces without the strong objection of the European powers. The war that ensued was, according to one historian, ‘the consequence of more than two years of fatal blundering in slow-motion by inept statesmen’.

It was also a war with widespread consequences for the balance of power in Europe–from the Black Sea to Bering Strait. For one spectacular consequence was the sale of Alaska to the United States to pay off Russia’s war debts.

Warning

Yalta is also (in)famous for the Big Three Conference between Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill in February 1945 when the shape of post-war Europe was drawn up on the table visitors can still see in the Livadia Palace. The emptiness of Stalin’s promises to give Poland free democratic elections remains a warning to western leaders seeking to respond to a Russia who had joined with Britain and the US in 1994 to assure the Ukraine of the sovereignty of her borders, when the newly independant nation gave up her nuclear arsenal.

History is being made once more in the Crimea. After twenty-five years of assuming that neo-liberalism had triumphed, we are facing new realities. The world-wide web of trade and finance was expected to tame the Russian bear and entice her into the club of nations respecting the conventions of international law. Instead western leaders have ensnared themselves in a world where principal trumps principle. Russian billions have been welcomed in western institutions with no questions asked. Who then is prepared to sacrifice trade for principle? Putin has exposed the void of the western soul.

As in past centuries, the consequences of these recent events in Crimea are likely to be around for a long time.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Very enlightening view on history seemingly repeating itself