Europe–an African perspective

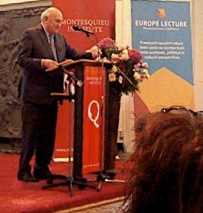

Europe ignored Africa to her own peril. That was the clear message in The Hague on Friday evening from Nobel Prize winner Frederik de Klerk, who oversaw with Nelson Mandela the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa.

Europe needed Africa, and Africa needed a strong Europe, he stressed. Sadly, however, Europe was not delivering.

What de Klerk himself was delivering was this year’s Europe Lecture, offering perspectives on Europe’s world significance from prominent speakers. From our second-row seats in the packed Klooster Kerk, my wife and I heard the former president describe himself as a Hugenot descendent who strongly identified with his continent as an African. Europeans sometimes had forgotten their enormous impact on the rest of the world over the past five centuries, he continued, colonising and populating three of the world’s six inhabited continents and conquering all but a mere dozen countries of the world.

The withdrawing tide of European rule had left country after country floundering on the beach of independence, he explained. Many African countries had thus developed a love-hate relationship with their former colonisers, and had tried to play Europe off against the Soviet bloc. That of course changed after the demise of communism. Still, European diplomats had shocked his successor, President Mbeki, telling him in 2003 that the EU had no place for Africa in its global strategic assessment.

The ensuing decade had reshaped the landscape significantly, he reminded us, and Europe’s global prestige had waned in the wake of the Euro crisis and her struggling integration project. The emergence of new economic giants, the BRICS* countries, had made Africa once more an arena for global strategic interest.

Icebergs

De Klerk offered his analysis of the north-south division in Europe, where the richer nations did not want to bail out the south without controlling their spending; and the poorer countries felt forced into an economic straightjacket compromising their national sovereingty.

The essence of the problem, he offered, was that the EU was like a giant tanker with 28 captains on the bridge. Only united decision-making could avoid the threatening icebergs.

One such iceberg was Europe’s looming demographic crisis. Birthrates well below the sustainable figure of 2.1(Italy and Spain were 1.4; Germany and Poland, 1.3), meant that populations could shrink by 75% by the century’s end. Massive migration from outside was the only solution–but would fundamentally change the character of Europe.

Yet the world needed a Europe strengthened by the ideals that established the EU in the first place, a Europe that could counterbalance the United States on the one hand and the growing influence of China and India on the other.

A strong Europe was in Africa’s best interests too, he declared. Europe still was Africa’s biggest investor and trading partner. China, despite all the media attention, was still only the sixth largest investor in the continent.

Mistake

Africans however often felt they remained on the perifery of Europe’s worldview. Trade negotiations between Africa and Europe had seemingly stalled, despite Jose Manuel Barroso’s call for ambitious, proactive trade engagements with strategic partners.

The exclusion of Africa from Europe’s strategic planning was, de Klerk judged, a mistake. Africa’s potential was enormous and at 5% over the next two years, according to the World Bank, would remain one of the fastest economically growing regions in the world. Sub-Sahara Africa was the largest area of under-developed real estate in the world, with enormous mineral resources and a virtually untapped agricultural potential.

Yet there was another important reason why Europe’s interested lay in the future success of Africa, he ventured. More than any other continent, Europe needed a prosperous Africa to stem the tide of African refugees caused by crop failures, and economic or political crises.

But Europe would need to resolve its own current challenges to become strong and play its proper role in the world, he warned. European leaders had to restore confidence in the guiding vision and convince Euro-sceptics to rejoin the project. And they had to address the potentially catastrophic demographic crisis.

For whatever happened, he concluded, events in Europe would continue to influence the future of Africa. And what happened in Africa would significantly impact Europe.

As we filed out of the church into the dark autumn evening, I thought of Robert Schuman’s original declaration of May 9, 1950, in which he specifically identified the development of the African continent as one of Europe’s essential tasks. Once more, we have ignored the founding father’s wisdom to our peril.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

*BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

This Post Has 0 Comments