The miraculous spiral

The red sandstone Munster in Basel overlooks the majestic sweep of the Rhine River as it turns northward to define the border between France and Germany.

Basel was one of our last stopovers of the Continental Heritage Tour which ended this weekend. Our group attended an organ recital in the Munster, which had also overseen an historic turn in church history early in the 16th century as Erasmus, Oecolampadius and later Calvin gave Basel a vital role in shaping the Swiss Reformation.

Although Erasmus helped birth the Reformation through publishing his ‘new improved’ Greek translation of the New Testament in Basel in 1516, he eventually took distance from the movement after the outburst of violence and smashing of images and statues known as the Iconoclasm. He moved north to Freiburg in Germany for six years before returning to Basel where he died in 1536 and was laid to rest in the Munster.

Erasmus had befriended a younger preacher-scholar named Johann Heussgen who also adopted a Greek name, Oecolampadius (house lamp). He became a great help to Erasmus in his translation work, and his preaching persuaded the city leaders in Basel to adopt the Reformation.

Oecolampadius died soon after Erasmus moved to Freiburg and is immortalised in a red sandstone statue in the Munster. It is often said that what Melancthon was to Luther and Beza to Calvin, so was Oecolampadius to Zwingli; a major player for the Reformation in Basel and Switzerland.

Magnificent order

It was in Basel that a young 26-year-old lawyer-theologian named Jean Calvin found refuge from the persecution of Protestants in France, and published his Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536, before moving to Geneva to promote the Reformation movement there.

On our tour we had arrived in Basel directly from Geneva, where we had reflected on Calvin’s legacy not only in church government and theology, but in education, civil government, compassionate society, family life–and in the rise of modern science.

For Calvin focused on the magnificent order of a universe which operated without the slightest sign of confusion according to the laws which God sustained and governed all things at all times. The ‘ordo naturae’ formed one grand machine displaying God’s wonderful wisdom, power and goodness, according to Calvin.

This was how modern science arose out of the biblical conception of reality. New horizons were opened. The picture of the world as an organism was replaced by that of the world as a mechanism. Max Weber observed that such ‘secularisation’ or ‘disenchantment’ of nature was the essential prerequisite for the development of modern science.

Spira Mirabilis

On our tour we had encountered numerous names of early scientists who, because of their faith in a God of order, went searching for God’s fingerprints in creation: Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Blaise Pascal and Johannes Kepler, among others. All were keen theologians whose faith fed their scientific interest.

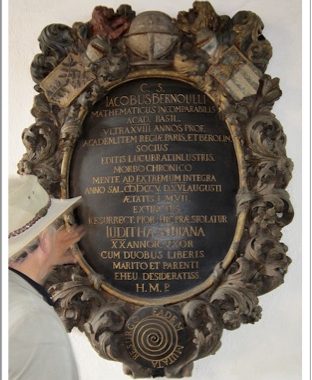

A tombstone in the Basel Munster drew our attention to a name well-known among mathematicians for his probability theory and developments in calculus: Jacob Bernoulli.

From a Protestant family famous for producing mathematicians, Bernoulli descended from refugees fleeing religious persecution in the Catholic Low Countries.

Bernoulli held the chair of mathematics at Basel University until his death in 1705. He wanted a logarithmic spiral and the motto Eadem mutata resurgo (I rise again changed and yet the same) engraved on his gravestone. He was fascinated by the ‘magical’ or ‘miraculous’ properties of the logarithmic spiral in which the size of the spiral increased but its shape remained unaltered with each successive curve. He dubbed it the spira mirabilis, seeing in it ‘a symbol of the human body, which after all its changes, even after death, will be restored to its exact and perfect self’.

The spira mirabilis can be observed in creation from spiral arms of galaxies to patterns of tropical cyclones, from nautilus shells to sunflower heads, from a hawk’s predatory trajection to the path of an insect approaching light.

Bernoulli would turn in his grave however if he could see what any mathematically-minded visitor to the Munster today can see. By error, his gravestone was carved with an Archimedean spiral, in which distances between the curves are constant, while the turnings of a logarithmic spiral increase in geometric progression.

And thus the symbolism of resurrection was sadly lost.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments