From pope to fellow pilgrim

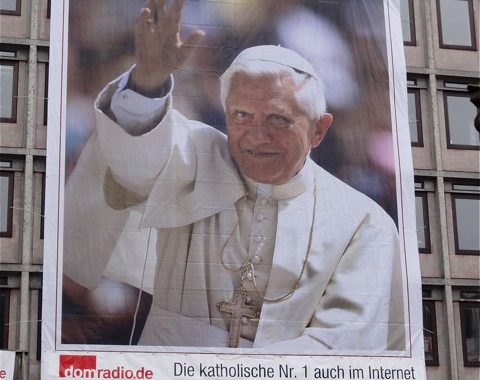

Visitors approaching Cologne Cathedral this past week saw the retired pope waving from a huge photo hanging on a building opposite what was once the world’s tallest structure. One word expressed appreciation on behalf of millions around the world : ‘Danke’.

To which I added a hearty ‘amen’ when passing through that city the day after the historic abdication.

As a non-Catholic, I’m not comfortable with all that the pope stands for, such as his invocation of ‘the maternal intercession of Mary, Mother of God and of the Church’, in his farewell address last Thursday.

But as a fellow Christian, I am deeply grateful for all that Joseph Ratzinger has done for the Christian faith over the past nearly eight years as pope, and prior to that as perhaps the world’s most influential living Christian thinker.

Some describe Benedict XVI as the most intellectual pope to sit in ‘Peter’s Chair’ for centuries. It may have been a great challenge to fill the shoes of his popular and charismatic predecessor who had been so instrumental in the fall of communism. But it will be no small task for the next pope to measure up to Benedict’s significant legacy.

While John Paul II contended with communism, Benedict has tried to engage the church with secularism, relativism and Islam. The root-cause of the intellectual, spiritual and social crises in Western culture as he saw it was rootlessness.

In ‘Without Roots’, one of his first books published during his papacy, he and his co-author Joseph Pera, the then-president of the Italian Senate, portrayed the future of a civilisation which had exchanged its own heritage and inheritance for a pot of secularist broth. In his quiet professorial manner, he warned about the consequences of embracing a culture of death: abortion, euthanasia, suicide, drastically falling birthrates and non-reproductive re-definitions of ‘marriage’.

Reason

In several key addresses, he countered the popular idea that faith and reason were incompatible and antithetical. To those who accused religion of being the source of all violence, he acknowledged that phases of history indeed showed ‘pathologies of faith’, when religion was misused to justify brutality and inhumanity. But the twentieth century alone, he argued, furnished overwhelming evidence of ‘pathologies of reason’ when so-called ‘scientific’ theories had resulted in suffering for many millions.

Again and again he returned to the problem of reason estranged from faith, a reason which deconstructed reality to that which was scientifically measurable. In his famous/notorious 2006 Regensburg lecture, the point of which was largely lost in the global uproar by offended Muslims who did their best to prove his very point, he was actually addressing former colleagues of the science faculty at his former university on the relationship between faith and reason. John’s gospel, he said, opened with: In the beginning was the ‘logos’… and the ‘logos’ was God. ‘Logos‘ meant both reason and word, a reason which was creative and capable of self-communication, he explained. Acting unreasonably therefore contradicted God’s nature.

Justification

On other occasions, such as in Paris in 2008, in London in 2010, in Berlin in 2011, he warned of losing confidence in reason’s power to know more-than-empirical truth.

Ratzinger’s dialogue with secular philosopher Jürgen Habermas the year before becoming pope surprised many by the degree of common ground found and prompted Habermas’ statement that secularized citizens must not ‘refuse their believing fellow citizens the right to make contributions in a religious language to public debates’.

Benedict should not be remembered for what he was against, but what he was for. His encyclicals on hope and love offered biblical guidance for the church’s ‘mission of truth to accomplish, in every time and circumstance, for a society that is attuned to man, to his dignity, to his vocation’.

He strove to prepare his people to become a ‘creative minority’ acting as memory, conscience and imagination in a post-Christian world.

Yet his greatest legacy may be more fully realised in 2017 on the 500th anniversary of that great rupture in Western Christendom known as the Reformation. For, more than anyone else, Ratzinger was responsible for the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification of 1999, when the Catholic and Lutheran churches were reconciled over the doctrinal dispute triggered by the Wittenberg monk. “Luther was right,” declared Benedict in an historic public audience at the Vatican in November 19, 2008.

Last week he told the crowds at Castel Gandolfo that from now on he would “simply be a pilgrim who is beginning his last phase of pilgrimage here on earth.”

To our fellow pilgrim, we also say: Danke!

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

This Post Has 0 Comments